Debra K. Davenport

Auditor General

Special Audit

Maricopa County

Special Health Care District

Performance Audit Division

March • 2009

REPORT NO. 09-03

A REPORT

TO THE

ARIZONA LEGISLATURE

The

Auditor

General

is appointed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, a bipartisan committee composed of five senators

and five representatives. Her mission is to provide independent and impartial information and specific recommendations to

improve the operations of state and local government entities. To this end, she provides financial audits and accounting services

to the State and political subdivisions, investigates possible misuse of public monies, and conducts performance audits of

school districts, state agencies, and the programs they administer.

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee

Audit Staff

Copies of the Auditor General’s reports are free.

You may request them by contacting us at:

Office of the Auditor General

2910 N. 44th Street, Suite 410 • Phoenix, AZ 85018 • (602) 553-0333

Additionally, many of our reports can be found in electronic format at:

www.azauditor.gov

MMeellaanniiee MM.. CChheessnneeyy

, Director

DDoott

RReeiinnhhaarrdd

, Manager and Contact Person

LLoorrii

BBaabbbbiitttt

, Team Leader

EEsstteellllaa

AArrrreeddoonnddoo KKaarrll

KKuulliicckk

BBrriiaann

MMiieellee RRiittaa

SSeettoo

RRoossee

TTaarrbbeellll CChheeyyaa

WWiillssoonn

Senator

TThhaayyeerr

VVeerrsscchhoooorr,,

Chair Representative

JJuuddyy

BBuurrggeess,,

Vice-Chair

Senator

PPaammeellaa

GGoorrmmaann

Representative

TToomm

BBoooonnee

Senator

JJoohhnn

HHuuppppeenntthhaall

Representative

CClloovveess

CCaammppbbeellll,,

JJrr..

Senator

RRiicchhaarrdd

MMiirraannddaa

Representative

RRiicchh

CCrraannddaallll

Senator

RReebbeeccccaa

RRiiooss

Representative

KKyyrrsstteenn

SSiinneemmaa

Senator

BBoobb

BBuurrnnss

(ex-officio) Representative

KKiirrkk

AAddaammss

(ex-officio)

DEBRA K. DAVENPORT, CP

A

AUDITOR GENERAL

STATE OF ARIZONA

OFFICE OF THE

AUDITOR GENERAL

WILLIAM THOMSON

DEPUTY AUDITOR GENERAL

2910 NORTH 44

th

STREET • SUITE 410 • PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85018 • (602) 553-0333 • FAX (602) 553-0051

March 11, 2009

Members of the Arizona Legislature

The Honorable Janice K. Brewer, Governor

Betsey Bayless, Chief Executive Officer

Maricopa Integrated Health System

Transmitted herewith is a report of the Auditor General, A Special Audit of the Maricopa

County Special Health Care District. This report is in response to Laws 2008, Chapter 288,

§22 and was conducted under the authority vested in the Auditor General by Arizona Revised

Statutes §41-1279.03. I am also transmitting with this report a copy of the Report Highlights

for this audit to provide a quick summary for your convenience.

As outlined in its response, the Maricopa County Special Health Care District agrees with

the findings and plans to implement all of the recommendations.

My staff and I will be pleased to discuss or clarify items in the report.

This report will be released to the public on March 12, 2009.

Sincerely,

Debbie Davenport

Auditor General

cc: Maricopa County Special Health Care District Board of Directors

Bill Bruno, Chairman Susan Gerard, Vice Chairman

Elbert Bicknell, Director Alice Lara, Director

Greg Patterson, Director

Attachment

The Office of the Auditor General has conducted a special audit of the Maricopa

County Special Health Care District (District), pursuant to Laws 2008, Chapter 288,

§22. This audit was conducted under the authority vested in the Auditor General by

Arizona Revised Statutes (A.R.S.) §41-1279.03.

In November 2003, Maricopa County voters approved the creation of a tax-levying

healthcare district; subsequently, voters approved a special healthcare district

governing board in the November 2004 election. On January 1, 2005, Maricopa

County, which was operating the healthcare system, transferred the system’s fiscal

and operational responsibilities to the new Maricopa County Special Health Care

District. The District consists of the District’s Board of Directors and an integrated

health system, which includes a teaching hospital, several other healthcare facilities,

and two health plans. In fiscal year 2008, the District had a total of over 400,000

inpatient admissions and outpatient visits.

As directed by the Legislature, this audit focuses on providing information in the

following areas of district operations:

The sources and uses of district funds, including amounts generated through

the District’s taxing authority (Chapter 1, pages 11 through 19).

The District’s financial condition and changes required to ensure financial

stability (Chapter 2, pages 21 through 31).

Management salaries (Chapter 3, pages 33 through 38).

Contract personnel and associated costs (Chapter 4, pages 39 through 48).

The amount of medical assistance provided to indigent individuals and policies

that have changed to restrict services to this population (Chapter 5, pages 49

through 53).

The amount of uncompensated care costs the District had annually in relation to

the amount provided before the District was formed and to the amounts other

hospitals in Arizona had (Chapter 6, pages 55 through 63).

Office of the Auditor General

SUMMARY

page i

Where applicable, the audit also makes recommendations for improvement.

District revenues (see pages 11 through 19)

The District receives revenue from various sources, and while the District’s revenue

increased about 34 percent from fiscal years 2006 to 2008, the proportion of each

revenue source remained relatively the same. In fiscal year 2008, more than 80

percent of the District’s total revenue of about $572 million continued to be from two

sources, patient service revenue and fixed monthly payments, known as capitation

payments, that it receives from the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System

(AHCCCS), which administers the State’s Medicaid program.

In fiscal year 2008, after patient revenues and capitation payments, the next largest

sources of revenue were property taxes (8 percent) and federal and state assistance

(8 percent). When voters approved the District’s creation, they also gave the District

authority to impose a secondary property tax. In fiscal year 2008, the District received

over $46 million in property tax revenue—the maximum allowed without approval

from voters for an override of the statutory levy limit. Most of the federal and state

revenues are reimbursements for costs that the District has already incurred for

specific patient populations, such as a federal program that reimburses teaching

hospitals for a portion of the costs incurred for training residents.

Financial stability (see pages 21 through 31)

The District’s financial stability has improved, but its plans for a new hospital highlight

the need for it to take additional steps to ensure future stability. When the District

inherited the health system from Maricopa County, the system was facing a financial

crisis from large numbers of nonpaying patients, falling profitability, critically low cash

levels, and obsolete infrastructure. Various financial indicators, such as total net

assets almost doubling from June 2005 to June 2008, show that the District’s

financial condition has improved. In addition, auditors’ analysis of nine financial

indicators, such as “days cash on hand,” shows that the District has improved in

eight of the nine areas.

1

However, for four of the areas, the District is not yet meeting

its goals. Further, other measures of financial stability point to ongoing concerns—

the District reported that its financial condition is not yet strong enough to obtain an

investment-grade bond rating and has older facilities, and the District’s total

expenses related to bad debt and charity care are also increasing, which means that

more money is being spent on patients who cannot afford the full cost of their

medical services.

State of Arizona

page ii

1

“Days cash on hand” represents the number of days an entity could pay expenses if revenues were eliminated.

The District has taken preliminary steps to plan for a new hospital and has plans to

improve its clinics—actions that, if carried out, may require the District to borrow

substantially. Auditors identified several actions the District can take to help ensure

future financial stability, in addition to the various initiatives the District already has

underway. These actions include continuing strategic planning efforts and monitoring

financial and operational performance, explaining financing options to its Board of

Directors, and enhancing its process to analyze which projects should be funded.

Executive salaries (see pages 33 through 38)

When compared with similar healthcare facilities nationally, salaries for the District’s

top five executive management positions are generally lower than reported median

salaries. For example, when compared to all types of hospitals and health systems

with similar net revenues, the District’s Chief Executive Officer’s annual salary of

$367,600 was lower than the reported median salaries by at least $232,500, and the

Chief Medical Officer’s annual salary of $315,100 was lower than the reported

median salaries by at least $15,600.

The District’s executives also receive other forms of compensation, including district

contributions for benefits such as medical and dental insurance and the Arizona

State Retirement System (ASRS), paid time off, and merit pay. In addition, three

executives had district monies deposited into supplemental retirement accounts

because their salaries exceeded the ASRS maximum salary amount of $230,000 for

ASRS contributions.

1

However, they do not receive perks such as automobile

allowances.

Contracting practices for healthcare personnel (see

pages 39 through 48)

In fiscal year 2008, the District’s two largest contracts were for doctors and temporary

nurses. The District contracts with a private corporation that supplies all the doctors

and allied healthcare providers for its hospital and healthcare facilities.

2

Although this

structure is generally similar to the physician personnel structures at other teaching

hospitals, it is also unique in that the District contracts with a private entity, while other

teaching hospitals commonly contract with local university medical schools. The

contract contains cost containment and quality control features such as quality

performance contract incentives. However, this contract is a sole-source contract that

the District inherited from Maricopa County in 2005, and the District has not re-

evaluated the staffing model provided through the contract or determined whether a

Office of the Auditor General

page iii

1

As of December 2008, district counsel indicated that the District had no intention of making further contributions to this

supplemental retirement savings plan for these three employees, at least through June 30, 2012.

2

According to district policy, allied healthcare professionals include professionals such as physician assistants, nurse

practitioners, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives.

sole-source contract is still necessary. The District should re-examine whether this

staffing model is still optimal.

The District also contracts for some nursing personnel, but unlike its physician

positions, most of the District’s nursing staff are district employees. The District will

always need to supplement its nursing staff with contract nurses because of factors

such as a nation-wide nursing shortage; however, to help control costs, the District

has worked to increase its own nursing staff. For example, between fiscal year 2005

and October 2008, the average number of contracted nurses used each month has

dropped from 109 to 35, whereas the monthly average number of district nurses has

increased from 611 to 823 during this same period.

Medical services to indigents (see pages 49 through 53)

Since its inception, the District has had a program to serve indigent individuals who

are not eligible for other healthcare programs, such as the State’s Medicaid program

administered by AHCCCS. The District’s eligibility requirements and payment

policies have changed over time, but the program has always offered both

emergency and nonemergency services, such as outpatient surgeries and doctor’s

visits when a patient is ill. During fiscal year 2008, the program served approximately

39,540 individuals and had about $32 million in uncompensated medical services

costs.

1

According to the District, uncompensated medical services costs, often

referred to as charity care, are services provided to uninsured, low-income, and

underinsured patients who are financially unable to satisfy their debt. However, under

the District’s program, now called Copa Care, all participants, based on income

levels, are expected to pay some of the service costs. Although the program served

more individuals in fiscal year 2008 than in fiscal year 2007, its uncompensated

medical services costs decreased by about $7.5 million. According to the District, the

reduction resulted from increased patient revenue and decreased operating costs.

Uncompensated care costs (see pages 55 through 63)

In fiscal year 2008, the District had approximately $87 million in uncompensated care

costs—that is, costs incurred in providing care to people the District does not expect

to receive payment from.

2

The federal government’s Medicaid Disproportionate

Share Hospital (DSH) Payments program reimburses states for a portion of these

costs. The DSH program not only provides support for uncompensated care, but

also helps hospitals deal with low Medicaid reimbursement rates that are frequently

less than hospitals’ costs. AHCCCS, the State’s Medicaid agency, administers this

State of Arizona

page iv

1

These uncompensated medical services costs are for the District’s charity care program only, and do not represent the

District’s total uncompensated care costs, which were approximately $87 million in fiscal year 2008 (see Chapter 6, pages

55 through 63).

2

This report does not include uncompensated care costs for public hospitals in other states as requested in the legislation

because auditors determined that states may have different methods for calculating uncompensated care costs, and

thus it is not reasonable to compare these costs from state to state.

program, which involves determining which hospitals qualify based on established

criteria, and then distributing to these hospitals the DSH monies the Legislature

appropriates.

In fiscal year 2008, Arizona received nearly $94 million in federal DSH monies.

AHCCCS distributed the monies as follows: approximately $4.2 million went to the

District, approximately $17.3 million went to the private hospitals, and approximately

$72 million was deposited in the State General Fund. In addition, AHCCCS

distributed approximately $9 million from the State General Fund to the private

hospitals, which is the required state match, and according to AHCCCS resulted in

a net deposit to the State General Fund of approximately $63 million of federal DSH

monies. The District believes it should receive a larger portion of the State’s DSH

funds because, as the State’s primary safety net hospital, it has the largest amount

of uncompensated care costs, which must be certified to draw down some of the

federal DSH monies.

Office of the Auditor General

page v

State of Arizona

page vi

Office of the Auditor General

TABLE OF CONTENTS

continued

page vii

Introduction & Background

1

Chapter 1: District revenues

11

Net patient service revenue

11

Capitation

14

Property tax

14

Federal and state assistance

15

County assistance

18

Chapter 2: Financial stability

21

District has shown signs of improved financial stability

21

District’s plans for capital projects highlight need for continued improvement

26

Improving financial stability involves maintaining current initiatives and

adding new ones

28

Recommendations

31

Chapter 3: Executive salaries

33

District executives’ salaries generally lower than counterparts’ nationally

33

Total compensation packages include standard benefits but not perks

35

District executives’ salaries less than those offered to contractors before

and after District’s inception

37

Chapter 4: Contracting practices for healthcare personnel

39

District contracts for some personnel services

39

MedPro contract contains quality-of-care and cost containment

requirements

41

District should re-evaluate its model for obtaining physician services

45

District uses contract nurses on limited basis

46

Recommendation

48

Office of the Auditor General

State of Arizona

TABLE OF CONTENTS

continued

page viii

Chapter 5: Medical services to indigents

49

Eligibility and program fees have changed over time

49

Program costs and population served

52

Chapter 6: Uncompensated care costs

55

Federal government helps states cover uncompensated care costs

55

AHCCCS administers Arizona’s DSH program

56

Arizona’s uncompensated care costs and DSH payment distributions

59

District believes it should receive more DSH money

62

Appendix A: Salary survey analysis methodology and

additional salary information

a-i

Appendix B: Methodology

b-i

Appendix C: Bibliography

c-i

Agency Response

Office of the Auditor General

TABLE OF CONTENTS

continued

page ix

Tables:

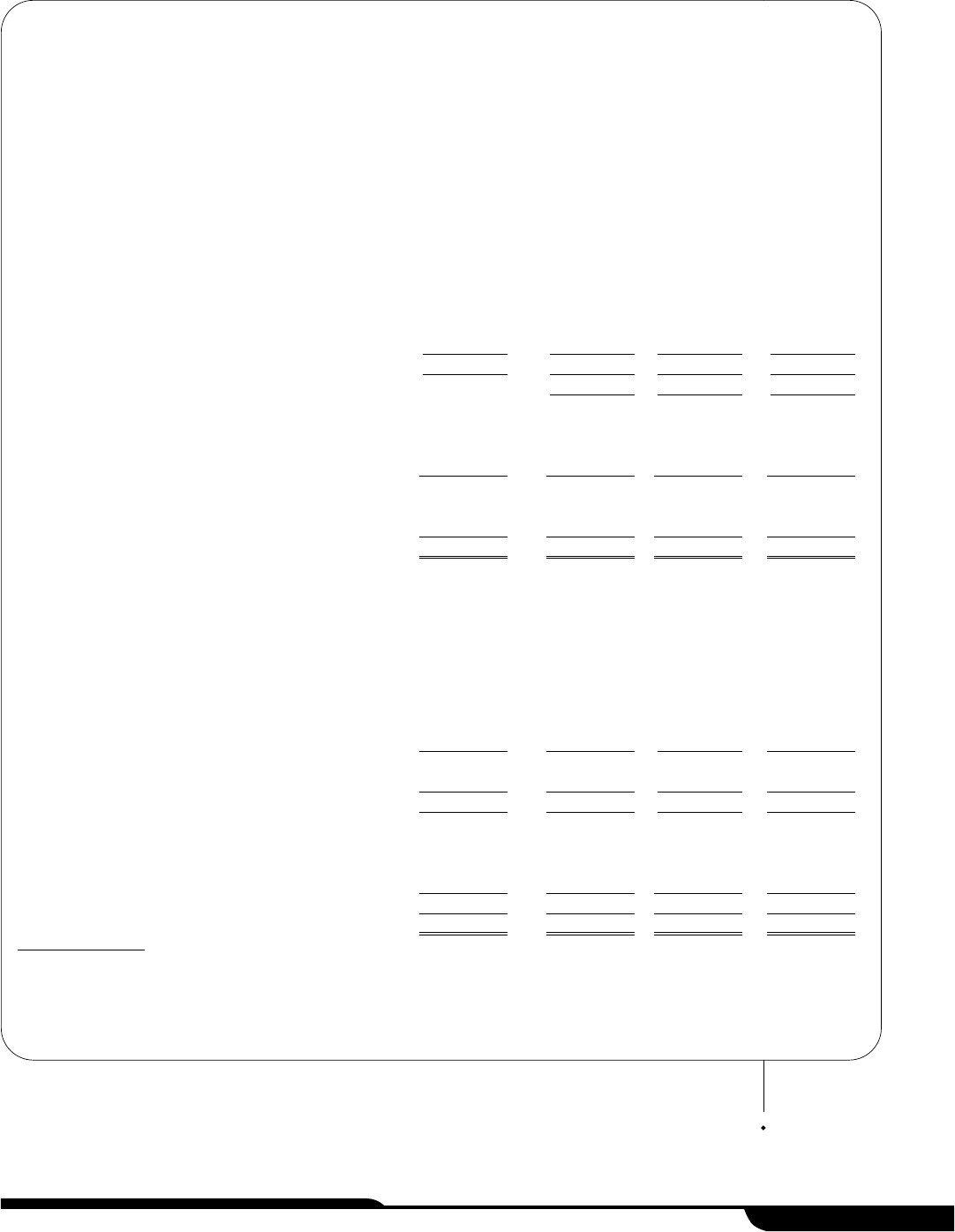

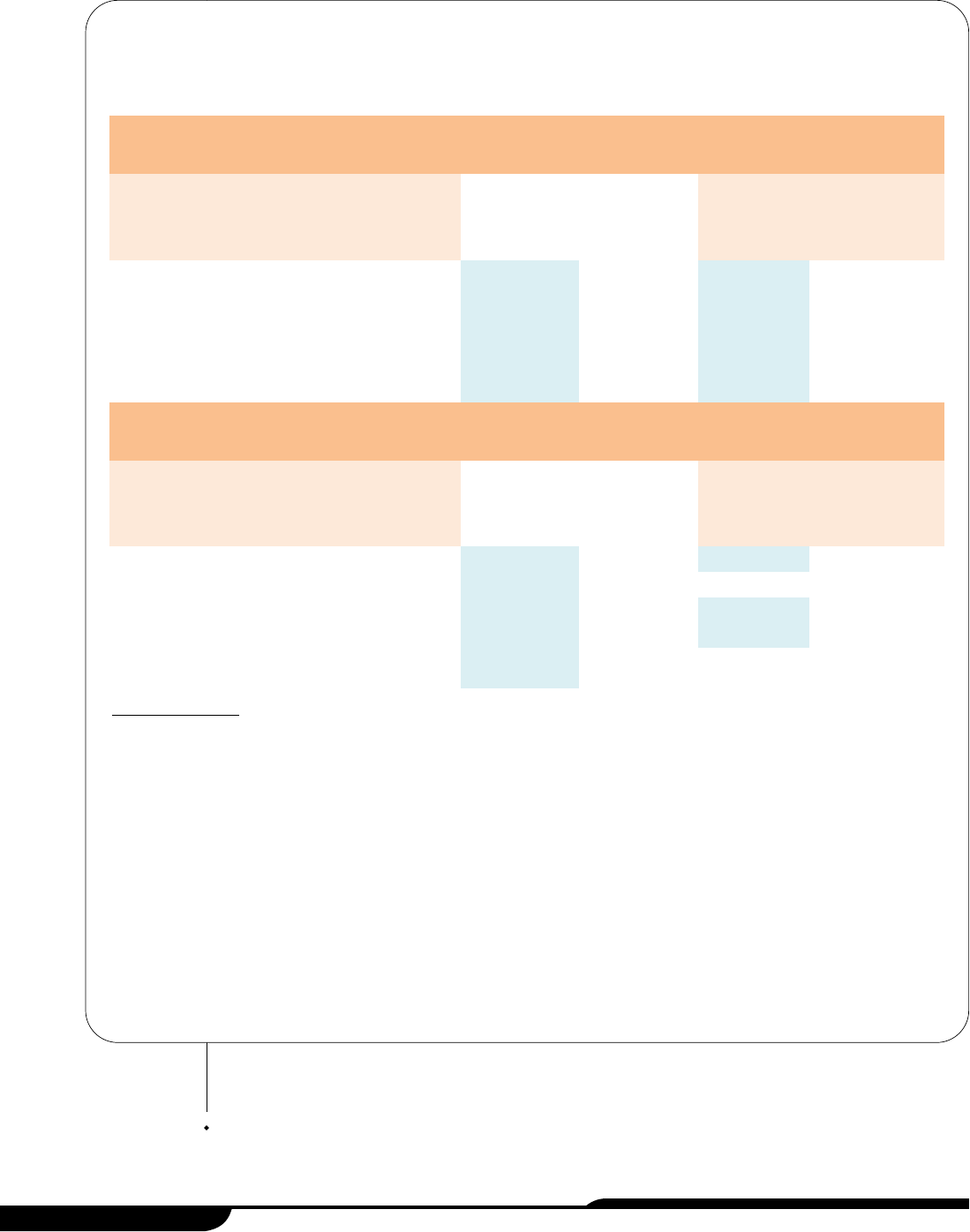

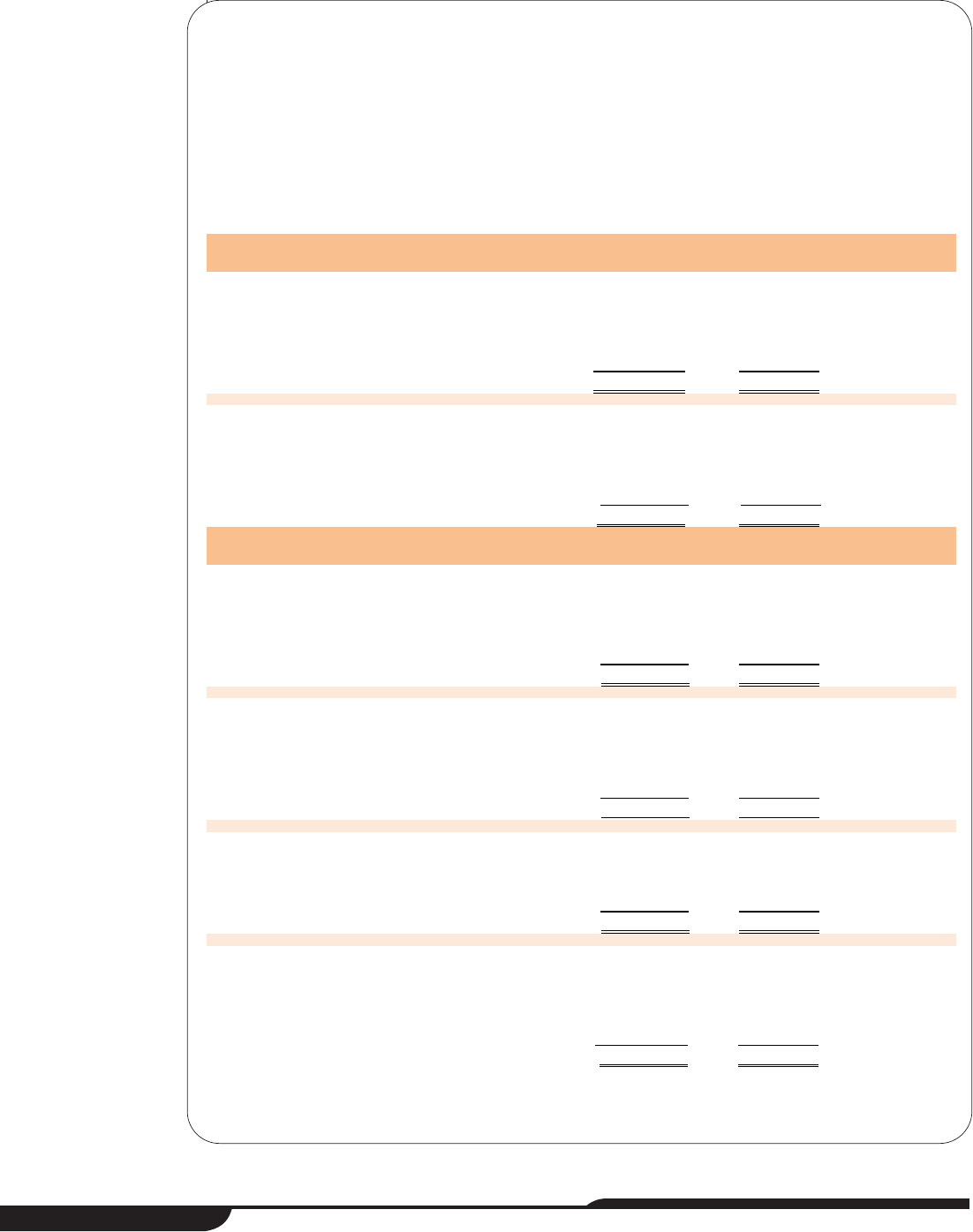

1 Statement of Net Assets

As of June 30, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008

(Unaudited)

7

2 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Assets

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

(Unaudited)

8

3 Schedule of Net Patient Service Revenue

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

(Unaudited)

12

4 Schedule of Federal and State Assistance

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

(Unaudited)

16

5 Schedule of Maricopa County Assistance

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

(Unaudited)

18

6 Profitability Ratios Compared to District Goals

Fiscal Years 2006 through 2008

(Unaudited)

23

7 Liquidity Ratios Compared to District Goals

Fiscal Years 2006 through 2008

(Unaudited)

24

8 Debt Ratios Compared to District Goals

Fiscal Years 2006 through 2008

(Unaudited)

25

9 Salary Comparison Tables

As of December 2008

(Unaudited)

34

State of Arizona

TABLE OF CONTENTS

continued

page x

Tables:

10 Comparison of Annual Contracted County and District

Executive Salaries to December 2008 District Salaries

(Unaudited)

38

11 MedPro Contract Services Quality Control Incentives

As of January 2009

44

12 Comparison of the Average Monthly

Number of District Nurses to Contracted Nurses

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2009

47

13 Charity Care Patients, Revenues, and Costs

Fiscal Years 2007 and 2008

(Unaudited)

52

14 Charity Care Program Patient Demographics

Fiscal Year 2008

(Unaudted)

53

15 Arizona Hospitals’ Uncompensated Care Costs Claimed and

Related DSH Reimbursements and Distributions

Fiscal Years 2008

(Unaudited)

58

16 Arizona Hospitals’ Uncompensated Care Costs and

Monies Received Related to DSH

Fiscal Years 2000 through 2007

(Unaudited)

60

16 Arizona Hospitals’ Uncompensated Care Costs and

Monies Received Related to DSH

Fiscal Years 2000 through 2007

(Unaudited)

(Concluded)

61

17 Additional Salary Comparison Information

As of December 2008

(Unaudited)

a-iv

State of Arizona

page xii

The Office of the Auditor General has conducted a special audit of the Maricopa

County Special Health Care District (District), pursuant to Laws 2008, Chapter 288,

§22. This audit was conducted under the authority vested in the Auditor General by

Arizona Revised Statutes (A.R.S.) §41-1279.03.

As directed by the Legislature, this audit focuses on providing information in the

following areas of district operations:

The sources and uses of district funds, including amounts generated through

the District’s taxing authority (Chapter 1, pages 11 through 19).

The District’s financial condition and changes required to ensure financial

stability (Chapter 2, pages 21 through 31).

Management salaries (Chapter 3, pages 33 through 38).

Contract personnel and associated costs (Chapter 4, pages 39 through 48).

The amount of medical assistance provided to indigent individuals and policies

that have changed to restrict services to this population (Chapter 5, pages 49

through 53).

The amount of uncompensated care provided by the District annually in relation

to the amount provided before the District was formed and to the amount

reported by other hospitals in Arizona (Chapter 6, pages 55 through 63).

Where applicable, the audit also makes recommendations for improvement.

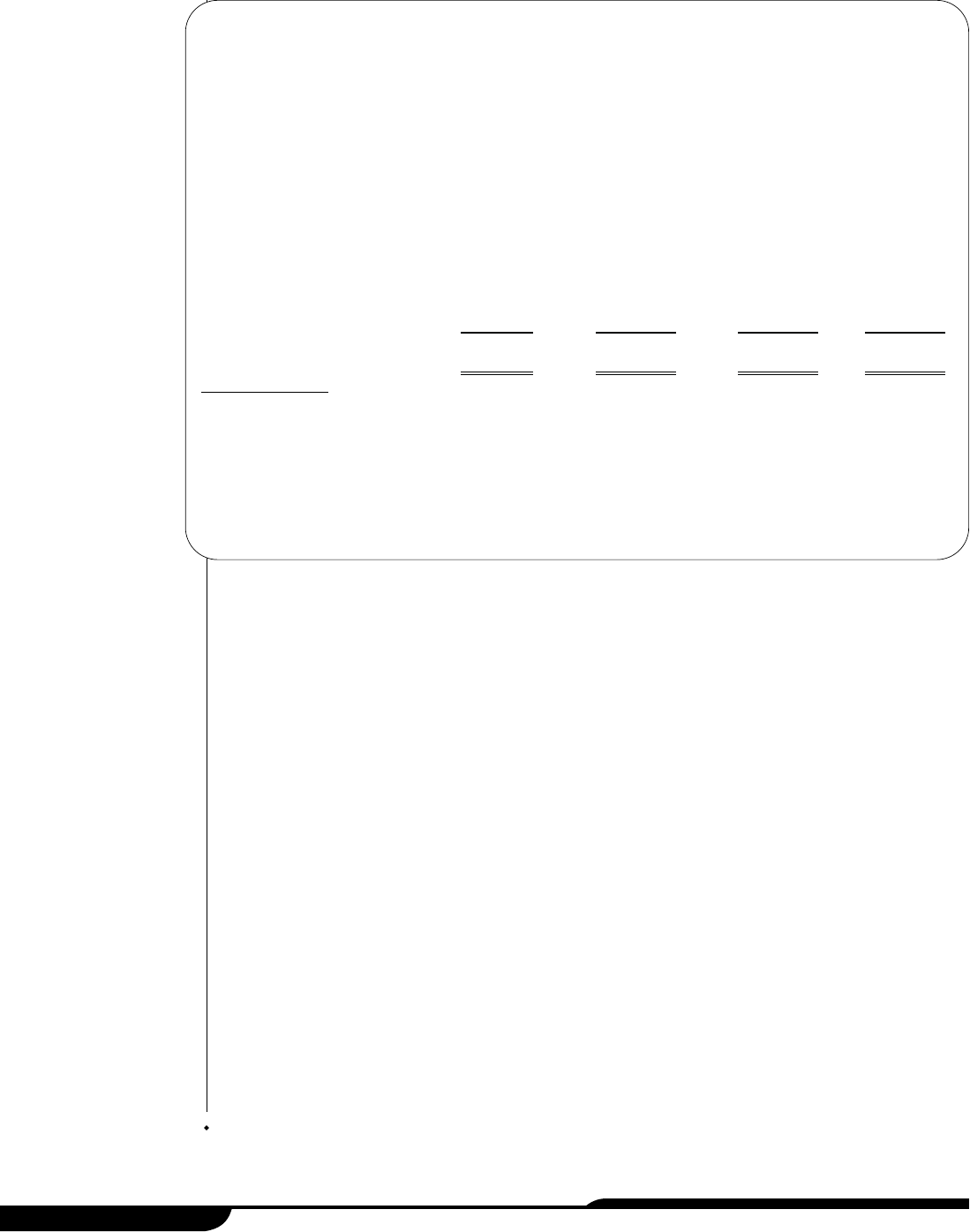

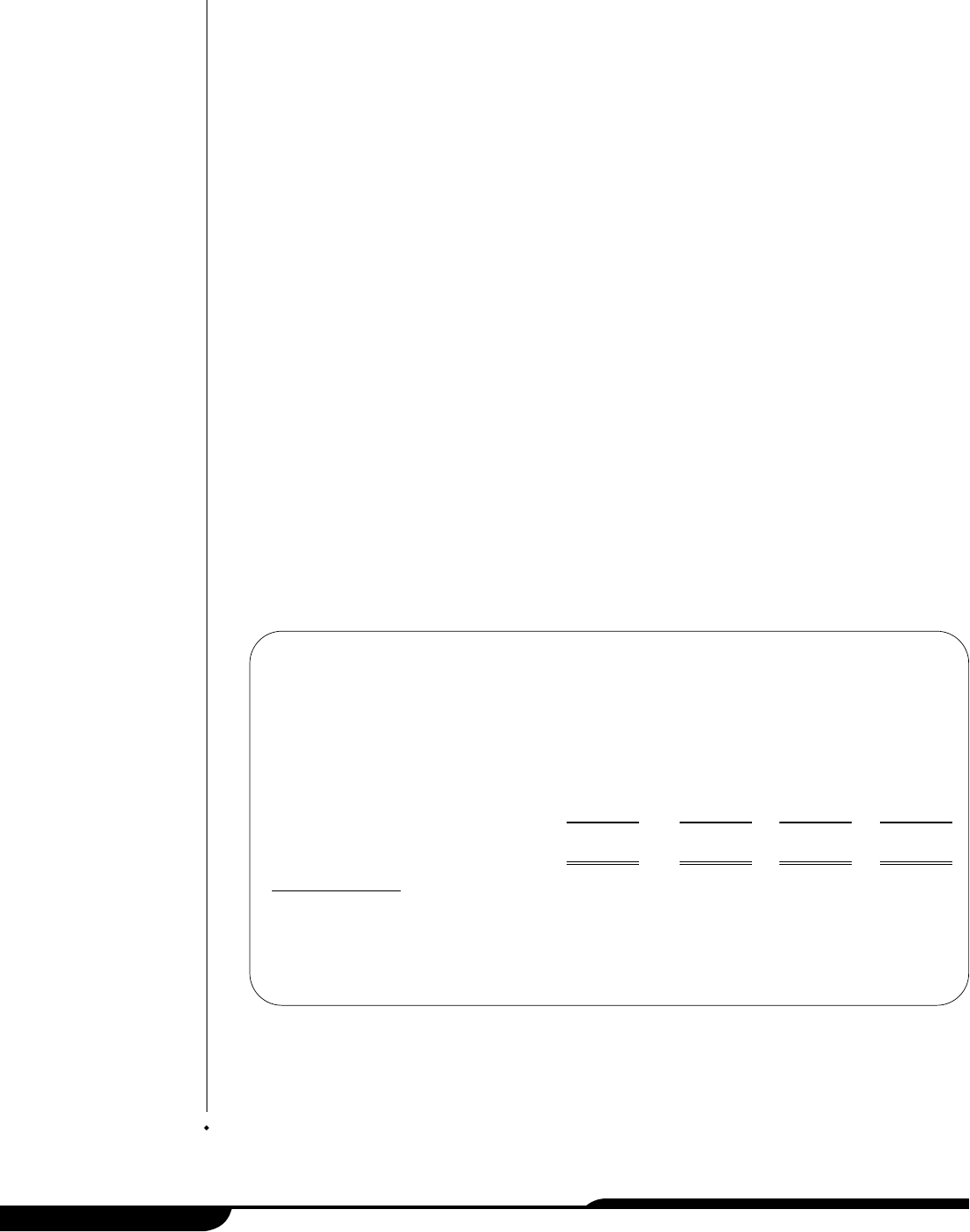

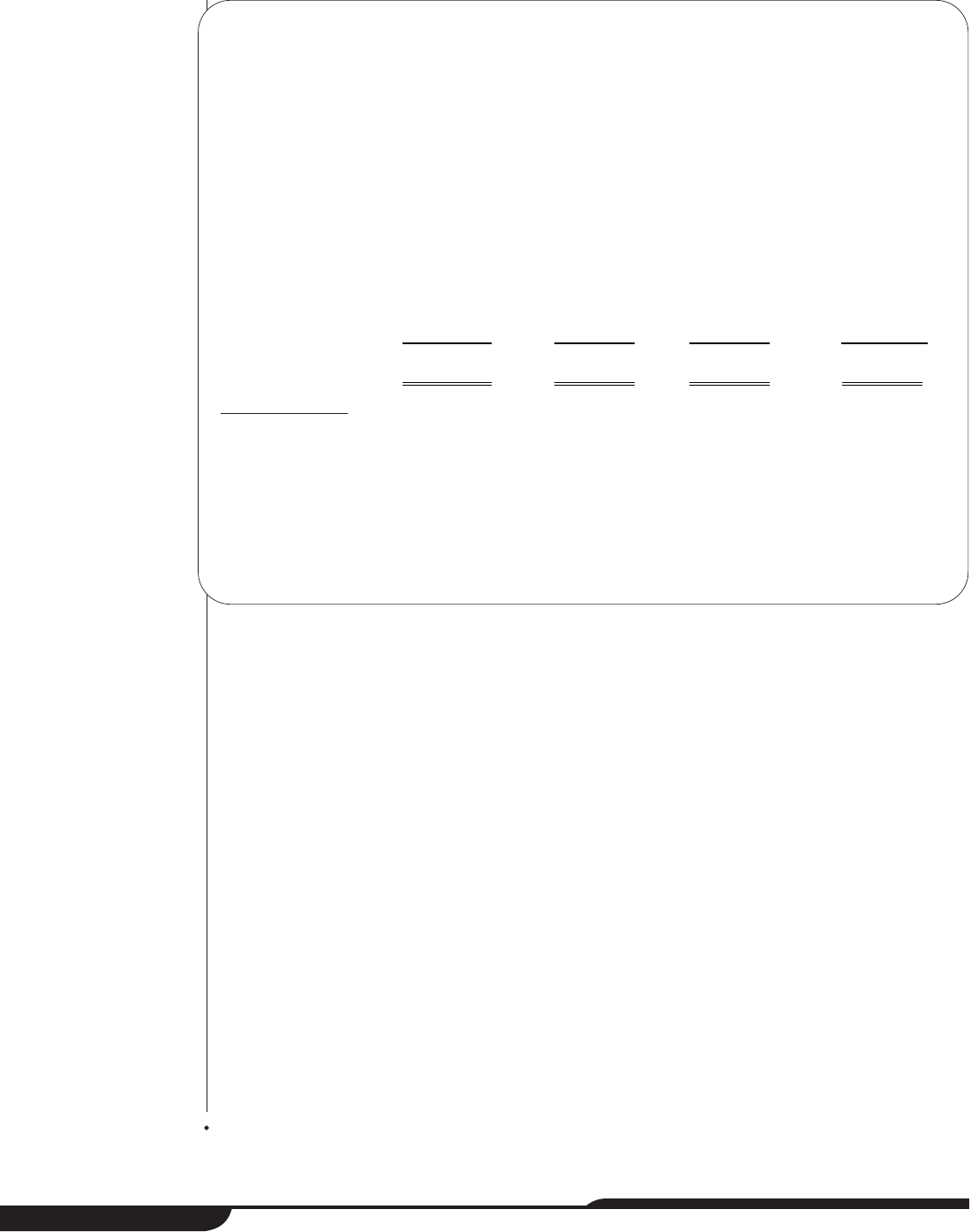

District history and system components

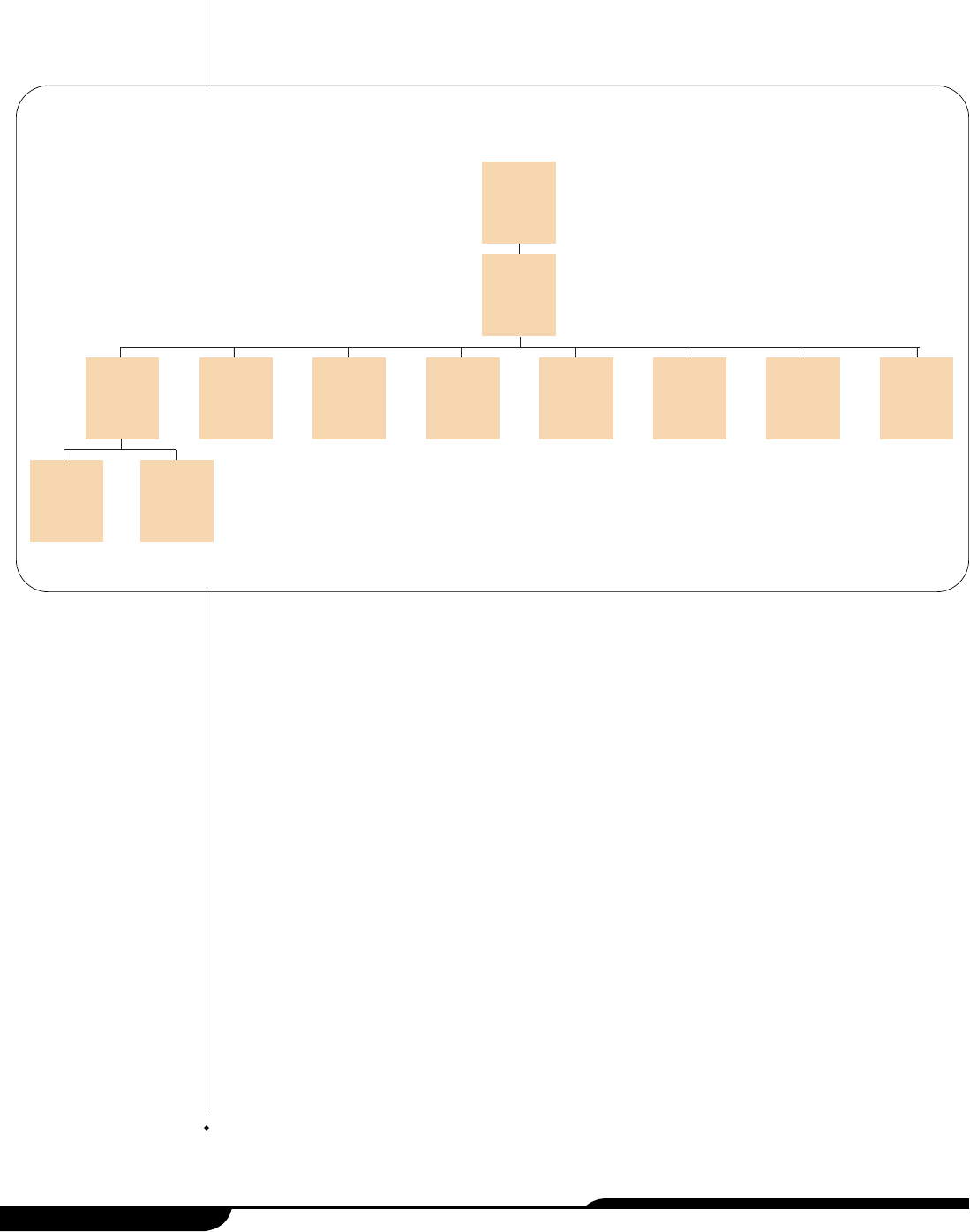

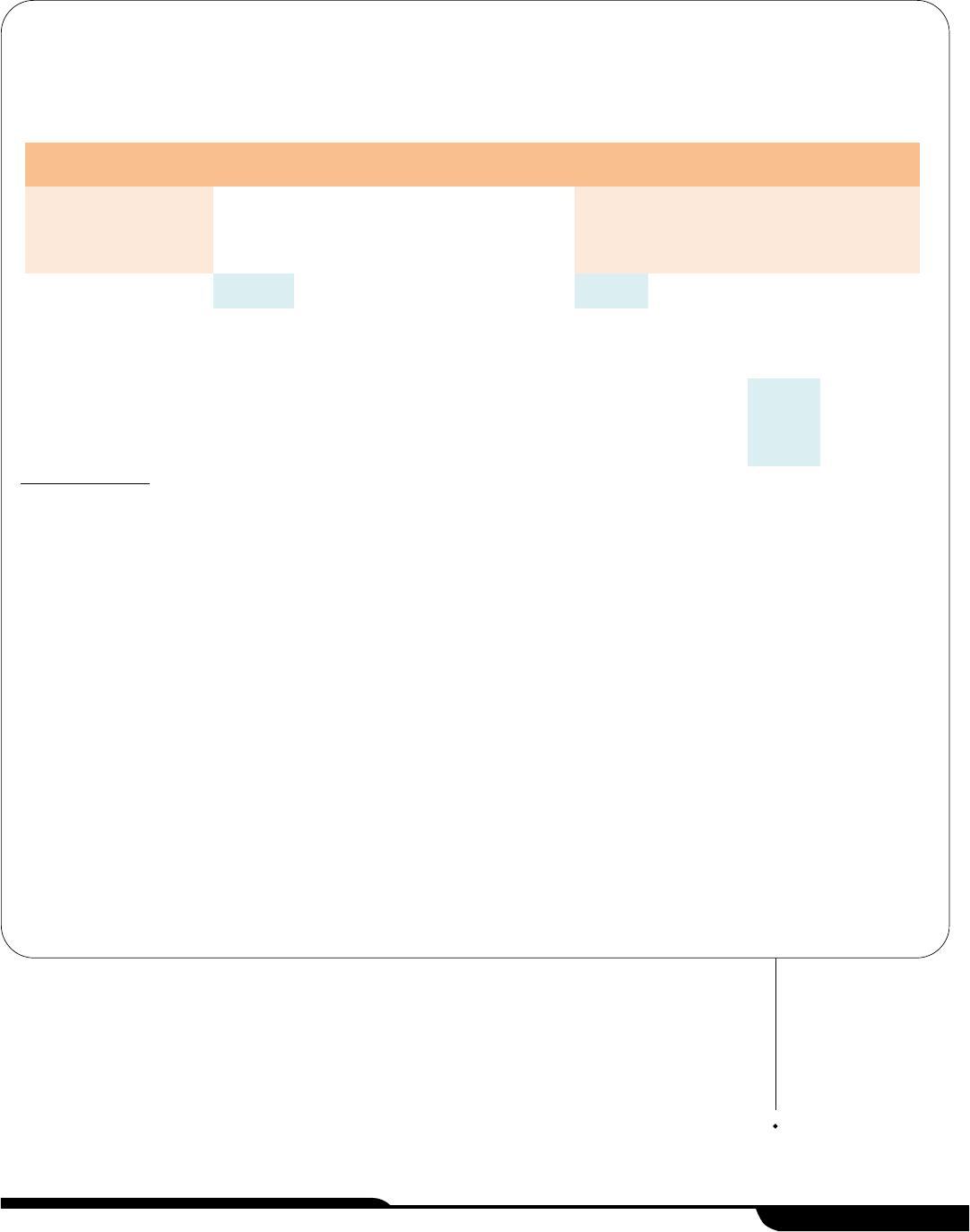

The Maricopa County Special Health Care District, as shown in Figure 1 (see page

2), consists of the District’s Board of Directors and an integrated health system, that

includes a hospital, several other healthcare facilities, and two health plans. In

November 2003, Maricopa County voters approved the creation of a tax-levying

healthcare district; subsequently, voters approved a special healthcare district

Office of the Auditor General

INTRODUCTION

& BACKGROUND

page 1

governing board in the November 2004 election. On January 1, 2005, Maricopa

County, which was operating the healthcare system, transferred the fiscal and

operational responsibilities for the system to the new District.

Maricopa County Special Health Care District Board of Directors

(Board)—The Maricopa County Special Health Care District is governed by a

five-member board of directors who are elected by Maricopa County voters and

serve 4-year terms. The Board’s responsibilities include appointing the District’s

Chief Executive Officer, monitoring the integrity of the District’s financial

statements, preparing budgets and capital plans, and reviewing and approving all

plans related to the healthcare of uninsured and underinsured patients. It also

reviews recommendations from the District’s Medical Staff Executive Committee

regarding appointment and reappointment of the District’s medical, dental, and

other healthcare staff.

Maricopa Integrated Health System (System)—The System consists of a

hospital, several other healthcare facilities, and two health plans. According to

district information, in fiscal year 2008, the System had over 21,000 inpatient

admissions and over 380,000 outpatient visits. Many of these visits were made by

patients who are eligible for the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System

(AHCCCS), which is the State’s Medicaid program. In addition, in fiscal year 2008,

over 39,500 patients eligible for the District’s charity care program, now called

Copa Care, accounted for 90,371, or over 22 percent, of total visits. The Copa Care

program provides emergency and nonemergency healthcare to medically

underserved individuals who do not qualify for other healthcare programs (see

Chapter 5, pages 49 through 53, for additional information).

State of Arizona

page 2

District Board of

Directors

Maricopa

Integrated Health

System

Maricopa

Medical Center

Behavioral

Health

Psychiatric

Centers

(2 centers)

Comprehensive

Healthcare

Center

Family Health

Centers

(11 centers)

Urgent Care

Center

Complete

Comfort Care

Maricopa

Health Plan

Maricopa Care

Advantage Plan

Arizona Burn

Center

Arizona

Children’s

Center

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of district Web site facility description documents and health plan contract as of December 2008.

Figure 1: Organizational Chart

As of December 2008

Specifically, the System operates under one hospital license for 717 beds and is

composed of:

MMaarriiccooppaa

MMeeddiiccaall

CCeenntteerr——

The Medical Center is a full-service teaching

hospital with more than 440 beds. The District’s hospital is an accredited

teaching facility where the physicians who treat patients also teach the over

200 residents in training who are employed to work at the District’s hospital

and other centers, such as the Arizona Burn Center (see sub-bullet below).

1

The hospital includes an adult and pediatric emergency care center, a

newborn intensive care unit, and the Arizona Children’s Center (see sub-bullet

below). In addition, the hospital provides healthcare to inmates from federal,

state, county, and tribal correctional institutions. According to the District, in

fiscal year 2008 it provided inpatient and outpatient care to 8,565 inmate

patients.

•

AArriizzoonnaa

BBuurrnn

CCeenntteerr——

The Burn Center, which is located within the

Medical Center, is a facility with more than 40 beds that is designated as

a regional burn center and provides inpatient and outpatient care for

burns and skin diseases. According to district information, in fiscal year

2008, it provided care to 763 patients admitted to its facility and 6,462

patients on an outpatient basis.

•

AArriizzoonnaa CChhiillddrreenn‘‘ss CCeenntteerr——

The Children’s Center, which is located within

the Medical Center, operates the 24-hour Pediatric Emergency

Department, a 12-bed Pediatric Intensive Care Unit that supplies inpatient

services for infants, children, and adolescents, and a 40-bed Neonatal

Intensive Care Unit that provides critical inpatient services for babies born

in the hospital as well as babies transported from across the Southwest.

According to the District, in fiscal year 2008, the Pediatric Emergency

Department provided care to nearly 17,000 patients.

BBeehhaavviioorraall hheeaalltthh ppssyycchhiiaattrriicc cceenntteerrss——

The District operates two behavioral

health psychiatric centers licensed for a total of 190 inpatient beds. According

to district information, in fiscal year 2008, the District treated 2,520 patients

admitted to its behavioral health psychiatric facilities. Inpatient services

include chemical dependency treatment, psychological testing, group and

family therapy, and medication education. According to district information, it

also provided outpatient care to 2,575 patients at its Desert Vista Behavioral

Health Center. Outpatient services include psychiatric evaluations, individual

and family therapy, and prescription of medication, if necessary.

CCoommpprreehheennssiivvee

HHeeaalltthhccaarree

CCeenntteerr——

The Healthcare Center provides primary

care for children and adults, including specialty services such as cardio-

pulmonary, dental, ear-nose-and-throat, internal medicine, dialysis, oncology,

orthopedics, ophthalmology, pediatrics, pharmacy, radiology, vascular

surgery, and women’s health services.

Office of the Auditor General

page 3

1

The Medical Center is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which is a private,

nonprofit council that evaluates and accredits medical residency programs in the United States.

CCoommmmuunniittyy-bbaasseedd

ffaammiillyy

hheeaalltthh

cceenntteerrss——

The District’s 11 community-based

family health centers provide primary care services for adults and children. In

fiscal year 2008, the health centers provided services to over 152,000 patients.

Some health centers also provide dental and pharmacy services. One of the

centers specializes in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) related medical care

for adults.

UUrrggeenntt CCaarree CCeenntteerr——

The System opened an Urgent Care Center in 2007 to

meet the needs of the residents who had relied on the former Phoenix Memorial

Hospital for urgent care services. Located in the Emergency Department on the

former Phoenix Memorial campus at 7th Avenue and Buckeye Road, the center,

according to the District, served over 18,000 patients in fiscal year 2008.

CCoommpplleettee CCoommffoorrtt CCaarree——

This program provides attendant care to elderly or

disabled clients in their homes. Services are tailored to individual needs and can

include cooking and cleaning, personal patient care, and companionship.

According to the District, in fiscal year 2008, over 952,000 hours of care were

provided to patients served through this program.

The System also contains two health plans:

MMaarriiccooppaa

HHeeaalltthh

PPllaann——

The Maricopa Health Plan (Plan) is one of six health

plans operating for Maricopa County residents that AHCCCS contracts with. The

Plan was in operation for nearly 20 years before the District was formed. Prior to

October 2005, Maricopa County operated the Plan. Starting in October 2005,

the District contracted with Tucson-based University Physicians Health Plans, a

division of University Physicians Healthcare, to manage the Plan. According to

the District, as of December 2008 the Plan had over 50,000 members.

1

According to district information, the Plan offers its members complete

healthcare services, including a choice of doctors, dentists, the Medical Center,

the District’s Family Health Centers, pharmacies, and emergency care in

Maricopa County.

MMaarriiccooppaa

CCaarree

AAddvvaannttaaggee——

This health plan (Plan) which began January 1,

2008, provides access to similar services as the Maricopa Health Plan. However,

this Plan is for a targeted special needs patient population of Medicare-eligible

patients who have greater needs because of their severe or chronic health

conditions. According to the District, this Plan had over 700 members as of

December 2008. University Physicians Healthcare and the District partnered in

a 50/50 joint venture to start the Maricopa Care Advantage Plan in order to

secure a Medicare Advantage Special Needs Program contract with the Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The District and University Physicians

Healthcare shared in startup costs. Maricopa Care Advantage is overseen by a

Board of Directors consisting of two members from the District and two

members from University Physicians Healthcare. It is managed by the same

State of Arizona

page 4

1

University Physicians Healthcare is a nonprofit corporation supporting the faculty doctors at the University of Arizona

College of Medicine. University Physicians Health Plans is a division of University Physicians Healthcare.

company that manages the District’s other health plan, University Physicians

Health Plans, a division of University Physicians Healthcare.

Accreditation

The District is accredited by a national healthcare accreditation organization. In

December 2008, the District received full accreditation from the Joint Commission, a

not-for-profit organization that evaluates and accredits healthcare programs in the

United States. This followed an earlier, September 2007 decision by the Joint

Commission to give the District a conditional accreditation, which means the

organization is not in substantial compliance with the Joint Commission’s standards

and it must remedy the identified problem areas. The Joint Commission identified 17

such areas during its 2007 accreditation review. According to a district official it found

that the District had remedied all 17 areas in the December 2008 review. For

example, the Joint Commission found that the District needed to ensure it has a

complete and accurate medical record for all patients served. The District has

addressed this by providing training and auditing records for accuracy.

Organization and staffing

The District has a five-member executive management team consisting of Chief

Executive, Financial, Operating, and Medical Officers, and a Senior Vice President

and Chief External Affairs Officer.

1,2

These positions are involved in directing,

controlling, evaluating, and developing organizational operations and resources to

ensure quality healthcare. District staff is composed of both permanent and

contracted employees. The District reported that it had an average of 3,630

permanent district employees per month in fiscal year 2008, including more than 800

nurses.

Although most staff are permanent employees, the District contracts for all of its

physicians and allied healthcare providers, along with some of its nurses. The District

contracts with a private corporation, Medical Professional Associates of Arizona

(MedPro), for all of its physician and allied healthcare provider services.

3

MedPro was

created in 1994 by physicians already employed by the Maricopa County Hospital

(for more information about MedPro, see Chapter 4, pages 39 through 48). Although

MedPro staff are subject to district board approval, MedPro is responsible for

providing the District’s physicians (medical doctors and doctors of osteopathy), and

many other credentialed healthcare professionals. As of January 2009, according to

The District contracts for

all of its physicians with

a private corporation,

MedPro.

Office of the Auditor General

page 5

1

The District’s Chief Medical Officer retired in February 2008 and as of December 2008, this position remained vacant.

2

Prior to December 2008, this position’s title was Vice-President Internal Development.

3

According to district policy, allied healthcare professionals include professionals such as physician assistants, nurse

practitioners, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives.

State of Arizona

page 6

MedPro, the District was contracting with them for the services of 205 physicians and

75 other healthcare providers. In addition, although the District has decreased the

number of temporary nurses it contracts out for by hiring more nurses permanently

(see Chapter 4, pages 39 through 48) from July through October 2008, the District

contracted for an average of 35 nurses per month.

Assets and revenue

The District’s assets have increased since it began operation on January 1, 2005. As

illustrated in Table 1 (see page 7), its assets have grown from $116.4 million at the

end of fiscal year 2005 to $262.6 million at the end of fiscal year 2008. As shown in

Table 2 (see page 8), in fiscal year 2005, some of the District’s assets consisted of

Maricopa County contributions. Specifically, Maricopa County contributed $6.3

million in cash and $62.8 million in other assets to the District in fiscal year 2005. Of

the $62.8 million in other assets, $32.8 million was capital assets, appraised at fair

market value on January 1, 2005, including property and equipment. However,

according to a district official, Maricopa County did not contribute the main hospital,

the Comprehensive Health Center, and one of the behavioral health psychiatric

centers to the District. The District pays Maricopa County an annual amount of $12

for leasing the main hospital and the behavioral health center, and $1.4 million for

leasing the Comprehensive Health Center, because Maricopa County has a long-

term debt obligation on this property.

Further, as shown in Table 2 (see page 8), the District receives revenue from various

sources and its revenue has also increased over time. In fiscal year 2008, the District

had operating revenue of more than $500 million. Sources of operating revenue

result from providing services through its normal operations and primarily consist of

patient revenue. The District also receives nonoperating revenue. Nonoperating

revenue is money derived from other sources, such as property taxes, grants, or

investments. For example, in fiscal year 2008, the District received over $46 million

from the property tax levy that was established when the District was formed, and

more than $7 million in state and federal grants.

Audit scope and objectives

As set forth in Laws 2008, Chapter 288, §22, audit work focused on six areas within

the District, and this report includes six chapters and recommendations as

appropriate, covering the areas in legislation. Specifically:

The Auditor General shall conduct a financial and performance audit of the

Maricopa Special Health Care District, which includes the Maricopa Integrated

In 3 years, district

assets have increased

by more than $140

million.

Office of the Auditor General

page 7

2005 2006 2007 2008

A

ssets

Current assets:

Cash and cash equivalents $ 7,972,267 $ 52,830,802 $ 4,305,003 $ 1,081,903

Short-term investments 60,258,608 69,991,227

Patient accounts receivable, net of allowances

1

61,035,690 50,339,440 44,448,598 52,376,462

AHCCCS medical education receivable 2,893,945 28,466,815

Health plans receivable 6,135,431 15,964,742 21,623,212

Other receivables 4,666,291 11,489,302 11,629,058 8,564,740

Supplies 6,168,973 4,882,944 4,961,198 5,498,031

Prepaid expenses 851,387 1,389,050 1,726,713 1,799,127

Estimated amounts due from third-party payors 440,000 1,138,020

Due from related parties 134,726

297,909 2,343,670 1,387,309

Total current assets

81,269,334

128,502,898

148,531,535

190,788,826

Long-term investments 14,564,020 2,070,750

Capital assets:

Land 4,090,000 4,090,000 4,090,000 4,090,000

Depreciable capital assets, net of accumulated

depreciation 30,676,580

40,352,728 56,999,346 67,141,497

Total capital assets, net of accumulated

depreciation 34,766,580 44,442,728 61,089,346 71,231,497

Other assets 373,912

4,330,997 1,584,815 612,874

Total assets $116,409,826

$191,840,643 $213,276,446 $262,633,197

Liabilities and net assets

Current liabilities:

Accounts payable $ 13,248,550 $ 21,935,749 $ 25,420,987 $ 24,059,017

Accrued payroll and employee benefits 12,058,797 12,036,622 14,766,906 17,915,732

Medical claims payable 17,350,990 20,167,480 20,569,645

Overpayments due to third-party payors 8,591,358 6,140,854 5,366,057 7,761,404

Other current liabilities 1,683,813 8,743,487 12,780,031 16,581,914

Current maturities of long-term debt and capital

leases 1,133,098

2,460,318 3,734,453 10,326,879

Total current liabilities 36,715,616 68,668,020 82,235,914 97,214,591

Long-term debt 7,821,144

30,726,575 33,390,390 24,642,537

Total liabilities 44,536,760

99,394,595 115,626,304 121,857,128

Net assets:

Invested in capital assets, net of related debt 27,733,755 63,477,195 41,898,763 49,655,337

Restricted for grants 290,665 712,178 459,687

Unrestricted 44,139,311

28,678,188 55,039,201 90,661,045

Total net assets 71,873,066

92,446,048 97,650,142 140,776,069

Total liabilities and net assets $116,409,826

$191,840,643 $213,276,446 $262,633,197

Table 1: Statement of Net Assets

As of June 30, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008

(Unaudited)

1

Patient accounts receivable balances were reported net of allowances for uncollectible accounts totaling $38,643,601 for 2005, $40,688,387 for

2006, $33,843,156 for 2007, and $40,999,432 for 2008.

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial statements and general ledgers for the 6-month period ended June 30, 2005,

and for fiscal years 2006 through 2008.

State of Arizona

page 8

2005

(6 months)

2006

2007

2008

Operating revenues:

Gross patient charges $417,135,447 $916,214,931 $1,110,290,697 $1,316,074,738

Less:

Internal transactions 108,519,701 130,451,738 145,604,380

Contractual adjustments 223,729,268 463,030,829 531,822,429 657,394,894

Charity care program 122,915,022 127,832,108

Bad debts 38,643,601

84,620,871 41,975,974 52,692,740

Net patient service revenue 154,762,578 260,043,530 283,125,534 332,550,616

Capitation 92,781,362 126,222,832 137,852,101

Other 5,539,544

19,880,749 25,383,389 40,925,469

Total operating revenues 160,302,122

372,705,641 434,731,755 511,328,186

Operating expenses:

Salaries and wages 69,618,101 145,476,202 165,654,356 194,842,815

Employee benefits 19,453,107 38,352,094 48,563,229 57,830,631

Purchased services 34,366,198 84,176,981 104,232,496 89,520,955

Medical claims 53,029,187 80,039,020 85,581,930

Supplies and other expenses 34,436,663 75,682,521 78,439,045 90,102,741

Depreciation 3,483,495

7,790,123 7,954,860 9,287,490

Total operating expenses

161,357,564

404,507,108

484,883,006

527,166,562

Operating loss (1,055,442

) (31,801,467) (50,151,251) (15,838,376)

Nonoperating revenues (expenses):

Property taxes 40,000,000 43,000,000 46,310,880

Noncapital grants 2,747,004 5,234,777 6,518,509 7,293,209

Noncapital subsidies from Maricopa County 1,773,948 3,547,900 3,547,896 3,547,896

Other nonoperating revenues 1,618,771 4,078,089 1,806,582 1,151,966

Investment income 256,013 1,717,452 2,988,257 2,890,090

Interest on debt (580,211

) (2,203,769) (2,505,899) (2,229,738)

Total nonoperating revenues 5,815,525

52,374,449 55,355,345 58,964,303

Income before contributions 4,760,083 20,572,982 5,204,094 43,125,927

Contributions from Maricopa County

2

:

Cash contributions 6,336,001

Other assets

3

62,838,753

Increase in net assets 73,934,837 20,572,982 5,204,094 43,125,927

Net assets, beginning of year (2,061,771)

71,873,066 92,446,048 97,650,142

Net assets, end of year $ 71,873,066

$ 92,446,048 $ 97,650,142 $ 140,776,069

Table 2: Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Assets

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

1

(Unaudited)

1

The District began operations on January 1, 2005, and therefore, fiscal year 2005 amounts represent activity for only 6 months.

2

Maricopa County transferred the assets of its Maricopa Integrated Health System to the newly created Special Health Care District on January 1,

2005.

3

Consists of patient and other accounts receivable, supplies, prepaid expenses, and property and equipment.

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial statements and general ledgers for the 6-month period ended June 30, 2005,

and for fiscal years 2006 through 2008.

Health System, pursuant to section §41-1278, Arizona Revised Statutes, and

provide a report to the Governor, the President of the Senate, and the Speaker

of the House of Representatives on or before March 15, 2009. The audit shall:

1. Identify and examine the current financial, administrative, and operational

issues of the District and identify changes required to ensure financial

stability (see Chapter 2, pages 21 through 31).

2. Identify the amount of funds generated through the taxing authority of the

District and how such funds are used (see Chapter 1, pages 11 through 19).

3. Examine the personnel structure, specifically management salaries,

contract personnel, and associated costs, and evaluate whether this

structure is consistent with and necessary for the execution of the statutorily

designated duties of the District (see Chapter 3 for executive management

salaries, pages 33 through 38, and Chapter 4 for contract personnel, pages

39 through 48).

4. Identify all sources of state and federal funding received by the District and

how these funds are used (see Chapter 1, pages 11 through 19).

5. Examine and identify the amount of medical assistance furnished to

indigent individuals who are uninsured and ineligible for Medicaid and other

health service programs and identify policies that have changed to restrict

services to this population (see Chapter 5, pages 49 through 53).

6. Examine the amount of uncompensated care provided on an annual basis

by the District and measure this amount in relation to the amount of

uncompensated care provided by facilities of the District before the

formation of the District, to the amount of uncompensated care provided by

facilities of the District before the implementation of Proposition 204, and to

the amount of uncompensated care reported by other private hospitals in

Arizona and public hospitals in other states (see Chapter 6, pages 55

through 63).

7. Recommend programmatic, administrative, financial, and operational

changes to ensure financial stability, improved accessibility, and effective

healthcare delivery (see recommendations, Chapter 2, page 31, and

Chapter 4, page 48).

The Auditor General and staff express appreciation to the District’s Board of

Directors, Chief Executive Officer, and staff for their cooperation and assistance

throughout the audit.

Office of the Auditor General

page 9

State of Arizona

page 10

District Revenues

The Maricopa County Special Health Care District (District) receives

revenues from various sources, including patient service revenue, the

District’s property tax, and federal assistance. From fiscal years 2006 to

2008, district revenues increased by about 34 percent, but during that

time, the percentage of revenue from each source remained relatively

consistent. Each year, more than 80 percent of district revenues primarily

came from two sources—patient service revenue and fixed monthly

payments (known as capitation)—received from the Arizona Health Care Cost

Containment System (AHCCCS), Arizona’s Medicaid agency.

1

Although a district

official indicated that all of the District’s revenues can be used for its operation, most

of the federal and state revenues are reimbursements for costs the District has

already incurred for specific patient populations.

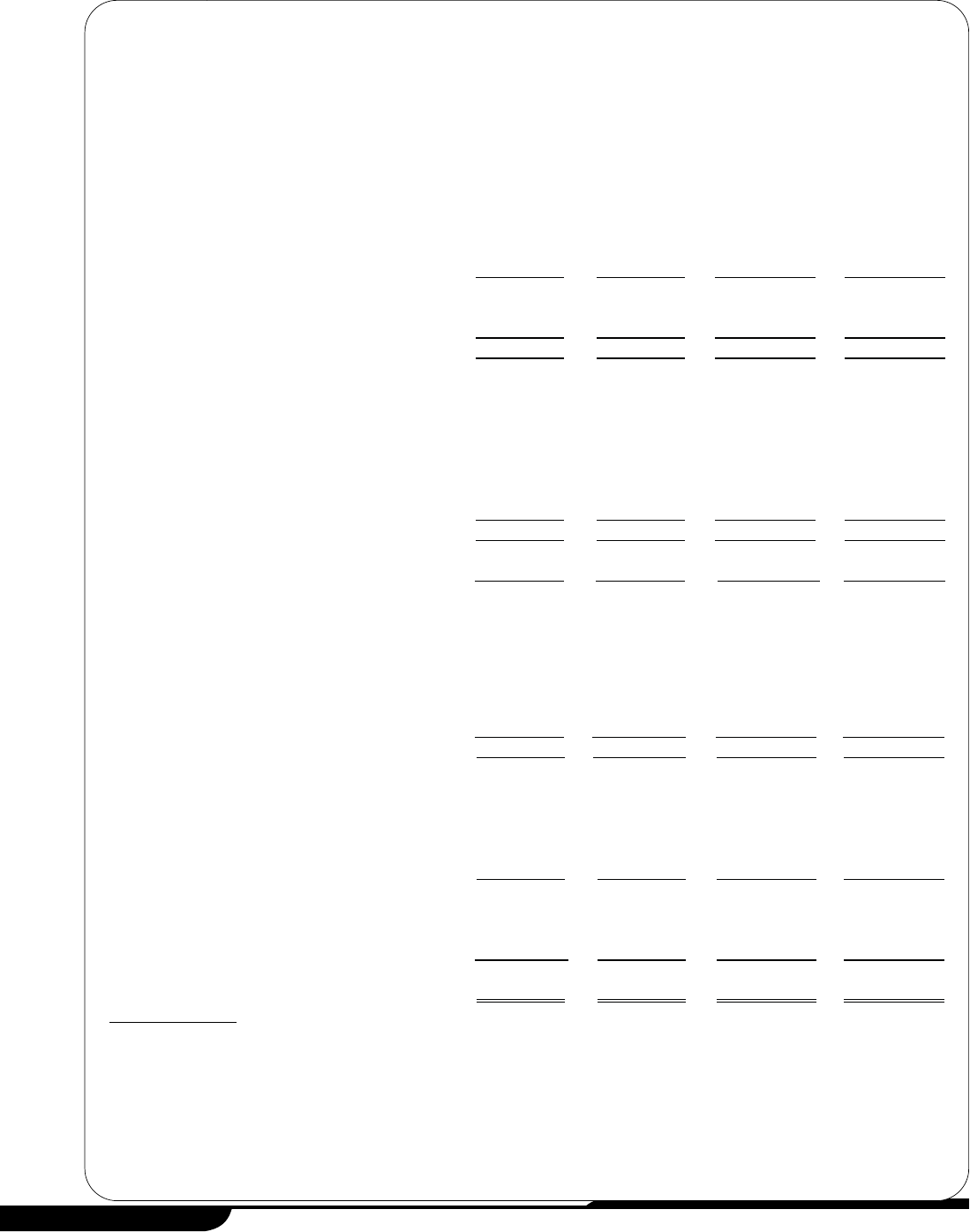

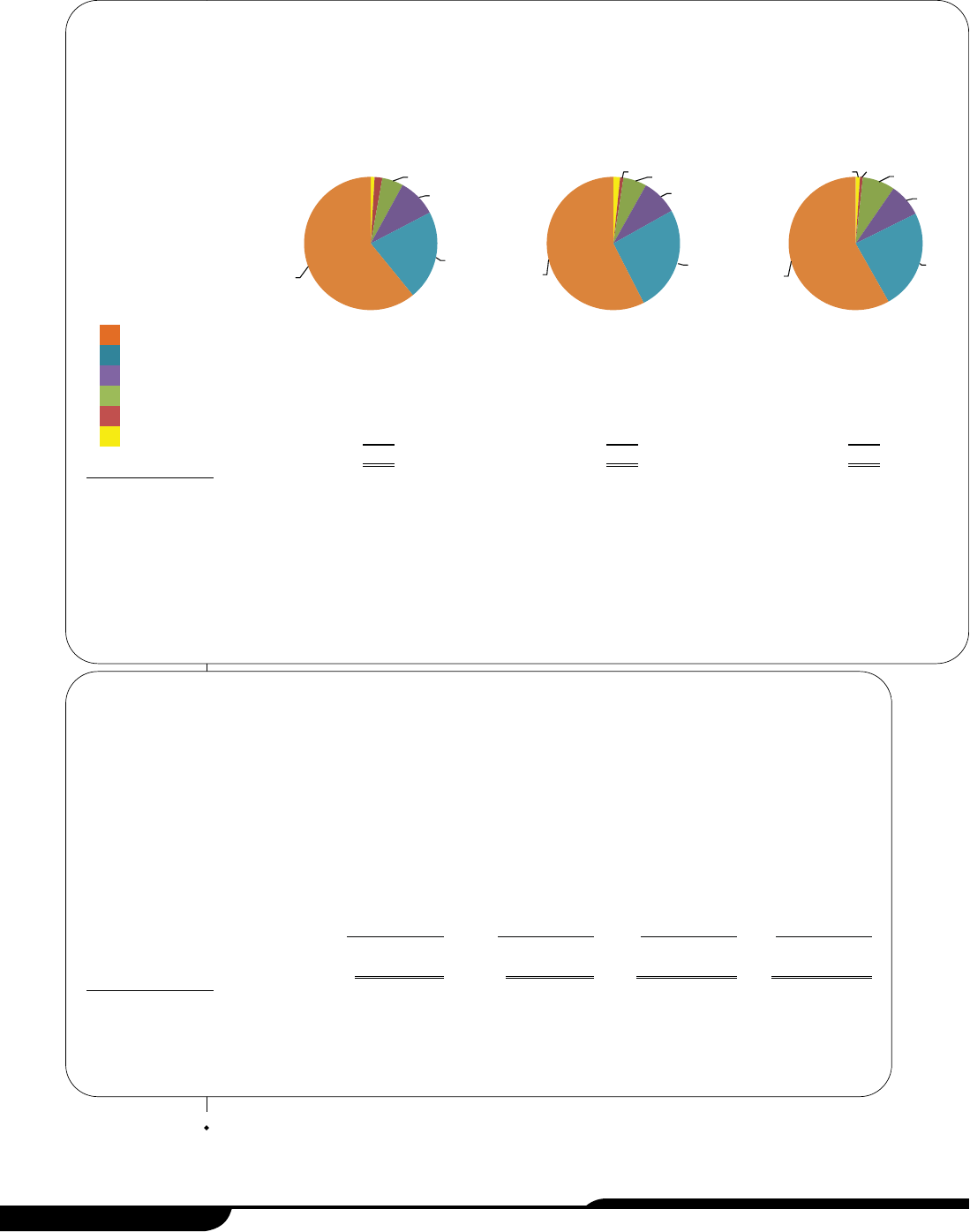

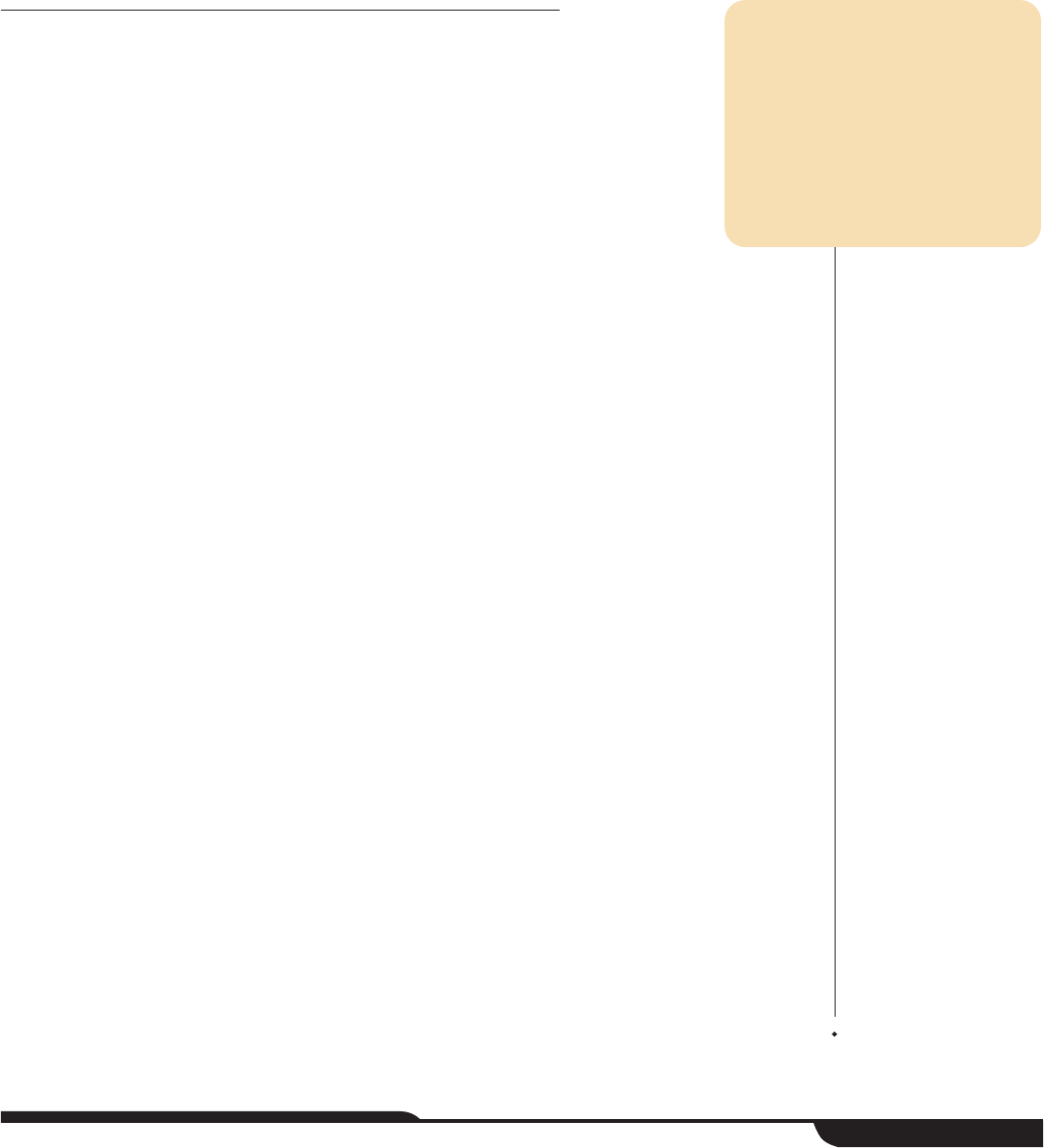

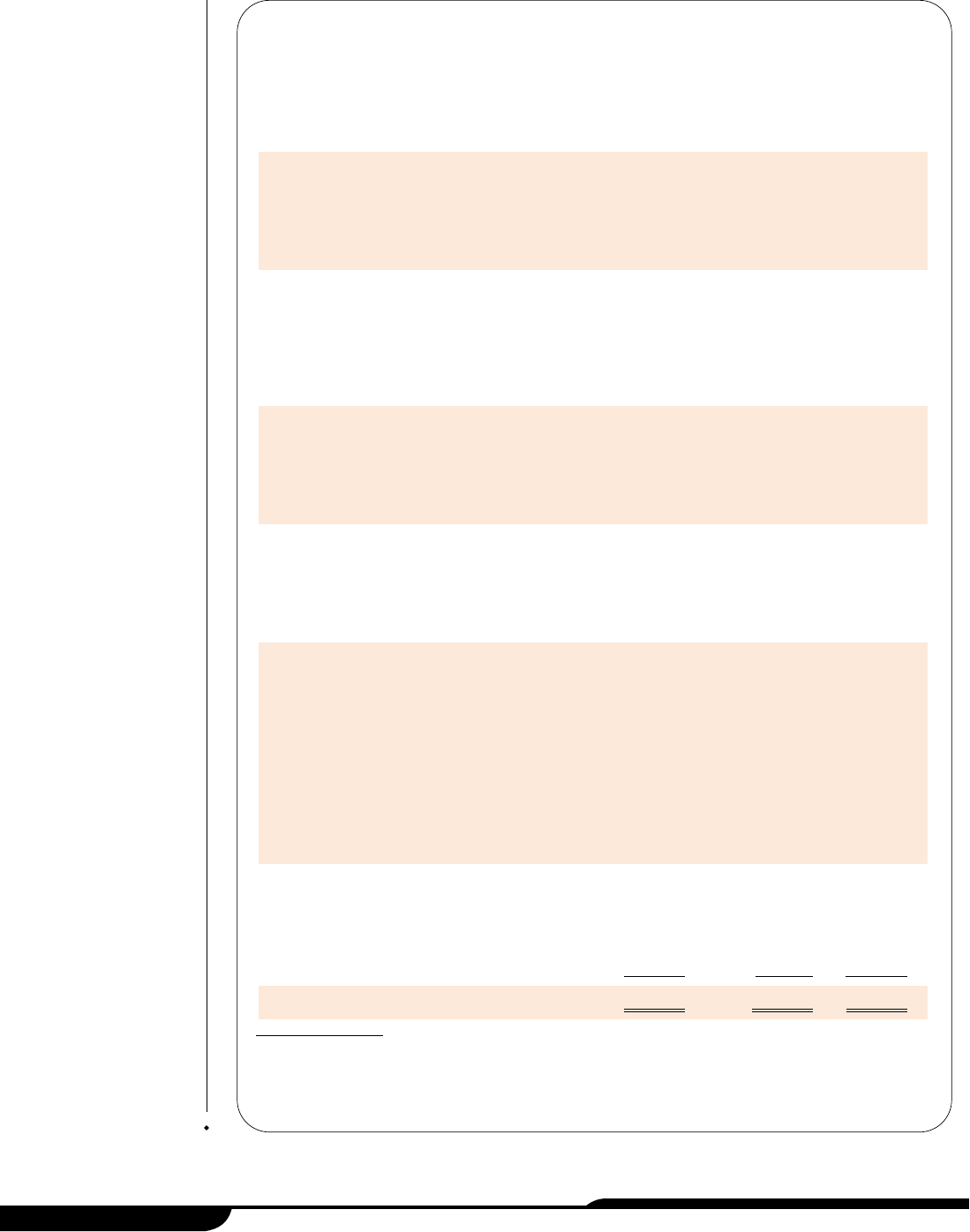

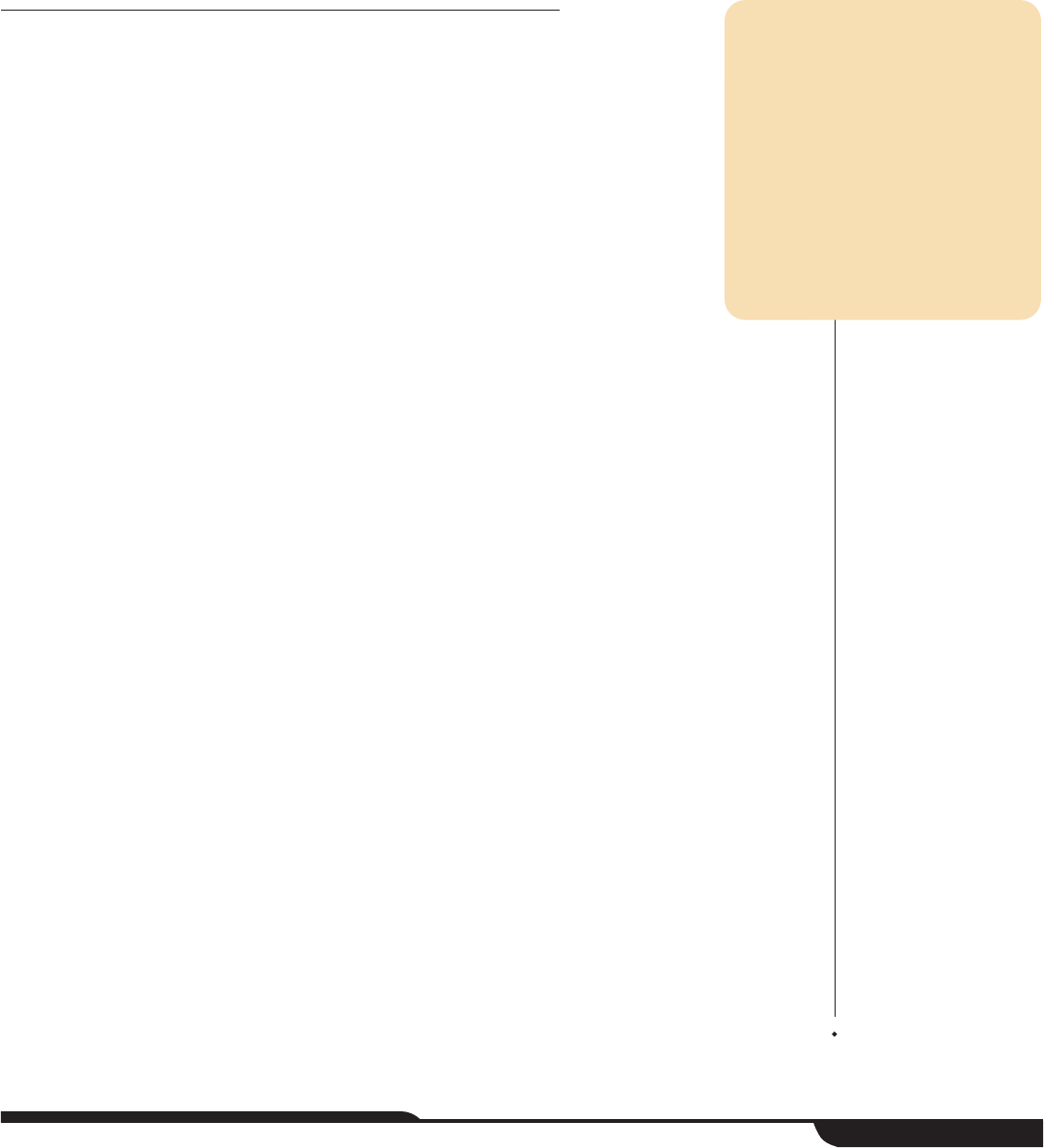

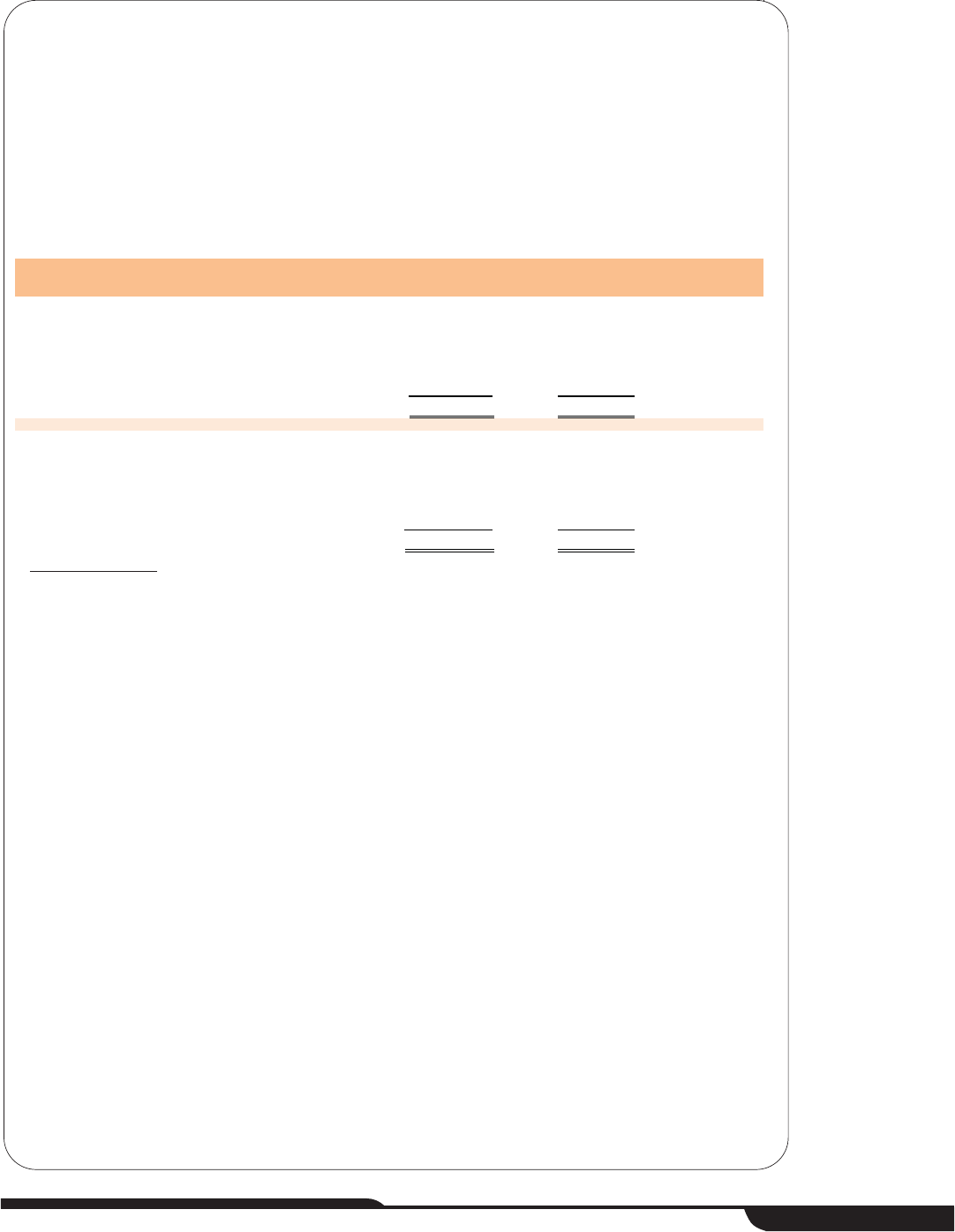

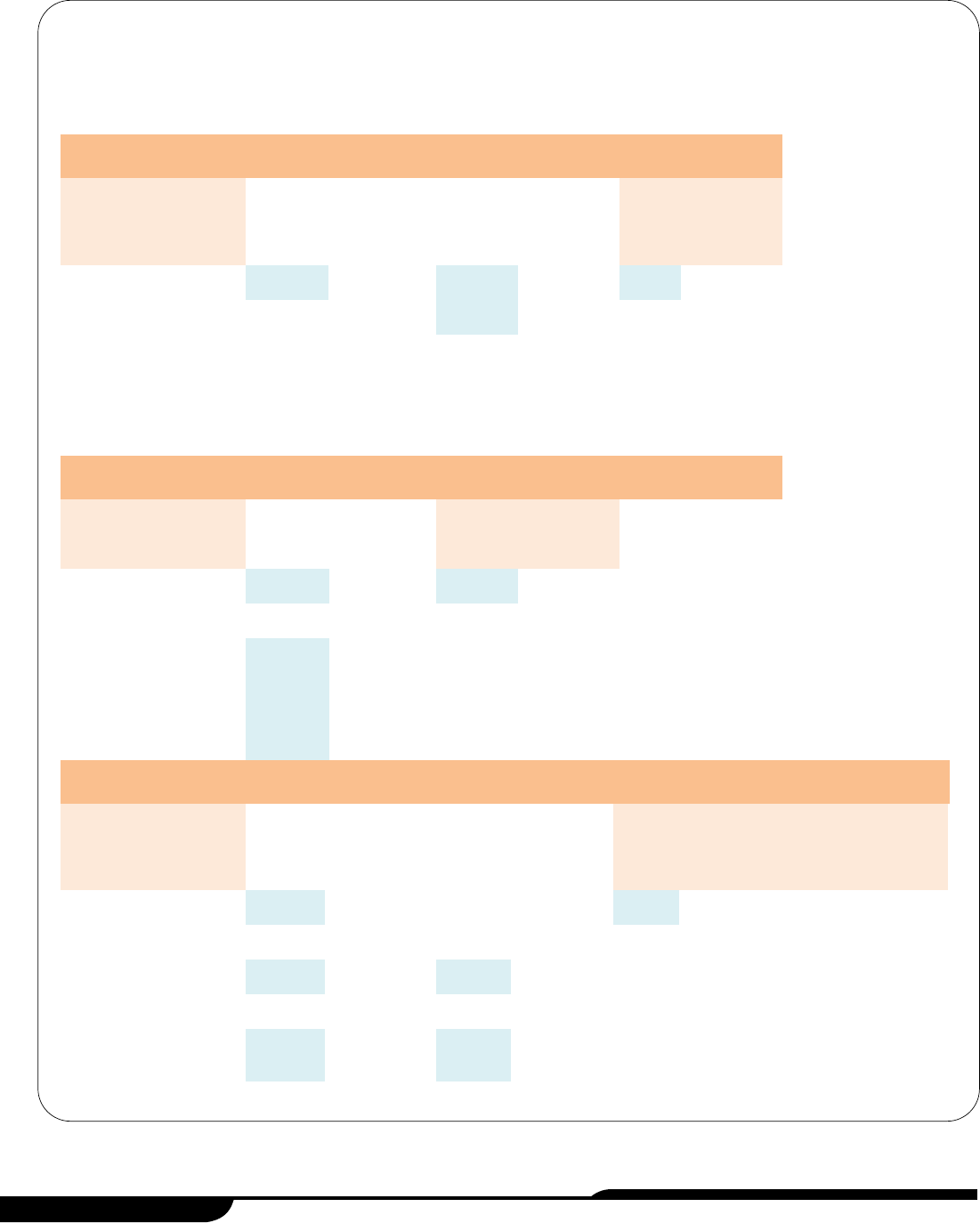

Figure 2 (see page 12) provides an overview of the revenues by source. The sections

that follow explain the five largest sources in further detail, including the amount the

District has received each year, the reasons for changes in the amounts over time,

and estimates of the amounts available for fiscal year 2009, if available. The Office of

the Auditor General is making no recommendations about the matters discussed in

this chapter.

Net patient service revenue

Net patient service revenue is total gross patient charges less various transactions

that reduce the amount of patient revenue received (see descriptions, page 13). As

shown in Table 3 (see page 12), it has increased from $260 million in fiscal year 2006

to $332.6 million in fiscal year 2008, an increase of about $72.6 million, or almost 28

percent, during that time period. According to a district official and budget

documents, the increase resulted from a higher service volume in clinic and urgent

care visits and outpatient services, and a slight rate increase on the AHCCCS and

Medicare accounts. The District expects net patient service revenue to increase by

more than 6 percent in fiscal year 2009.

Office of the Auditor General

page 11

CHAPTER 1

1

Patient service revenue is received from patients, and patients’ insurers such as Medicare, Workers’ Compensation, and

private insurance companies.

Legislative Item

The audit shall identify the

amount of funds generated

through the taxing authority of

the District and how such funds

are used; and identify all sources

of state and federal funding

received by the District and how

these funds are used.

State of Arizona

page 12

2005

(6 months)

2006 2007 2008

Gross patient charges $417,135,447 $916,214,931 $1,110,290,697 $1,316,074,738

Less:

Internal transactions 108,519,701 130,451,738 145,604,380

Contractual adjustments 223,729,268 463,030,829 531,822,429 657,394,894

Charity care program 122,915,022 127,832,108

Bad debts 38,643,601

84,620,871 41,975,974 52,692,740

Net patient service revenue $154,762,578

$260,043,530 $ 283,125,534 $ 332,550,616

Table 3: Schedule of Net Patient Service Revenue

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

1

(Unaudited)

1

Maricopa County transferred the system’s fiscal and operational responsibilities to the District on January 1, 2005, and therefore,

fiscal year 2005 amounts represent activity for only 6 months.

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial statements and general ledgers for the 6-month period ended June

30, 2005, and for fiscal years 2006 through 2008.

1%

1%

6%

9%

26%

57%

1%

1%

8%

8%

24%

58%

1%

2%

5%

9%

22%

61%

Figure 2: Revenues by Source

1

Fiscal Years 2006 through 2008

2

(In Millions)

(Unaudited)

1

Each revenue source is described on pages 11 through 19.

2

Maricopa County transferred the Maricopa Integrated Health Care System’s (system) fiscal and operational responsibilities to the District on

January 1, 2005, and therefore, fiscal year 2005 amounts represent activity for only 6 months. Therefore, fiscal year 2005 amounts are not

presented here because the data is not comparable to the 12-month data presented.

3

Amount consists of investment income, food sales, rental income, insurance proceeds for damaged property, and other miscellaneous sources.

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial statements and general ledgers for fiscal years 2006 through 2008.

Net patient service

$260

$283

$333

Capitation

93

126

138

Property tax 40 43

46

Federal and state assistance 22 28

45

County assistance 8 4

4

Other

3

4

8

6

$427

$492

$572

2006 2007 2008

Office of the Auditor General

page 13

Specifically, net patient service revenue is derived from the following components:

GGrroossss

ppaattiieenntt

cchhaarrggeess——

These charges represent the amount charged to

patients who received inpatient, outpatient, behavioral health, and other medical

services from the District’s hospital and health clinics.

IInntteerrnnaall

ttrraannssaaccttiioonnss——

These transactions are revenue amounts that must be

subtracted so that they are not counted twice. For example, the District operates

one of AHCCCS’ health plans and receives a monthly capitated amount as

revenue for every person enrolled. When an individual covered by this health

plan receives services from the District’s hospital, the revenue is also recorded

for the hospital, but it is then later subtracted to eliminate an internal transaction

since both the hospital and the health plan are part of the District. For fiscal years

2006 through 2008, the amount of these transactions was about 11 to 12 percent

of the total gross patient charges.

CCoonnttrraaccttuuaall aaddjjuussttmmeennttss——

These adjustments are discounts granted to

healthcare insurance organizations and government agencies based on agreed-

upon contract rates that are below the gross patient charges.

1

For fiscal years

2006 through 2008, the amount of these adjustments was about 48 to 51

percent of the total gross patient charges.

CChhaarriittyy ccaarree pprrooggrraamm——

This program, now called Copa Care, was created to

serve uninsured or underinsured patients who are ineligible for other programs

such as the State’s Medicaid program, administered by AHCCCS. Programs like

these are often called charity care programs because services are offered for

free or at a discounted rate. The District has established discounted fees for the

Copa Care program based on patients’ family size and income (see Chapter 5,

pages 49 through 53, for additional information). The discounts granted to this

patient population are deducted from gross patient charges. For fiscal years

2007 and 2008, these discounts amounted to about 10 to 11 percent of the total

gross patient charges. Although the District had a charity care program in fiscal

years 2005 and 2006, all of the discounts under the program at that time were

written off as bad debt (see next bullet).

BBaadd

ddeebbttss——

These deductions consist of medical services the District provided

and expected to receive payments for but did not. This happens when patients

are unable or unwilling to pay their bills. Also, patients’ insurance carriers dispute

their bills for many reasons such as service coverage, billing timeliness, and

patient eligibility. According to a district official, the District has an unwritten bad

debt policy that writes off certain accounts after they are 120 or 150 days past

due; however, the District continues to seek collection of the debts.

2

The total

bad debt amount was over 9 percent of the total gross patient charges in fiscal

1

Healthcare organizations and government agencies include AHCCCS, Medicare, private insurance companies, law

enforcement agencies, and workers’ compensation.

2

According to a district official, self-pay, Maricopa County Correctional Health, private insurer, lien, law enforcement, and

AHCCCS pending accounts are written off after 120 days past due. AHCCCS grievance, private managed care, Medicare

Special Needs, and Workers’ Compensation accounts are written off after 150 days past due.

year 2006. It decreased to 4 percent in fiscal years 2007 and 2008, when the Copa

Care program was implemented. However, for fiscal year 2009, a district official

indicated that the bad debt amount will increase by more than $7 million because

the District increased its gross patient charges.

Capitation

Capitation revenue is a fixed monthly advance payment that the District receives for

providing a full range of healthcare services, such as inpatient and outpatient services,

to AHCCCS and Medicare special needs members.

1

This revenue is restricted to

paying for medical costs incurred by AHCCCS and Medicare special needs members

and any allowable administrative costs. As shown in the textbox,

capitation revenue was $137.9 million in fiscal year 2008, an

increase of approximately $45 million, or nearly 49 percent, since

fiscal year 2006. According to a district official, the increase is

attributable to the fact that the District began the AHCCCS health

plan operation in October 2005 and therefore received capitation

revenue for only 9 months in fiscal year 2006. Since then the

AHCCCS health plan has had nearly an 18 percent rate increase.

In addition, during the second half of fiscal year 2008, the District

began a new health plan for Medicare special needs patients (see

Introduction and Background, pages 1 through 10, for additional

information) and received almost $1.3 million in capitation revenue for this plan.

According to district budget documents, the District expects increases in both

AHCCCS and Medicare capitation for fiscal year 2009.

Property tax

When Maricopa County voters approved the creation of the Special Health Care

District in the November 2003 election, the approval included authority to impose a

secondary property tax. Statute stipulated that for the first year the tax was authorized

and levied, it must not exceed an amount equal to $40 million, the maximum tax levy

limit for the base year.

2

Each subsequent year, the District’s levy amount can be

adjusted from its prior year’s levy amount based on a percentage equal to the rate of

change in the County’s levy limit between the current and prior years. The Maricopa

County Assessor calculates the rate of change and the District’s allowable levy limit for

each fiscal year. If the District wants to increase its property tax revenue beyond the

levy limit, voters must approve a tax levy limit override to increase the maximum

State of Arizona

page 14

1

Under the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003, Congress created a new type of

Medicare Advantage coordinated care plan focused on individuals with special needs. Special needs plans were allowed

to target enrollment to one or more types of special needs individuals identified by Congress as: (1) institutionalized; (2)

dually eligible; and/or (3) individuals with severe or disabling chronic conditions.

2

A.R.S. §48-5565.

Capitation

Fiscal Years 2006 through 2008

(Unaudited)

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial

statements and general ledgers for fiscal years 2006 through

2008.

2006 2007 2008

$92,781,362 $126,222,832 $137,852,101

Office of the Auditor General

page 15

allowable levy. For fiscal years 2006 through 2008, the District received the maximum

amount of its property tax revenue.

1

The District’s property tax revenue can be used to pay for

any operating costs, including maintaining and operating

the District’s facilities, payments for professional and other

services, and debt service, including principal and interest

on any bonds issued. As shown in the textbox, property tax

revenue was $46.3 million in fiscal year 2008, an increase of

over $6.3 million, or nearly 16 percent, since fiscal year

2006. Although tax rates have declined since 2006, the

District’s property tax revenue has increased because of

higher assessed property values in Maricopa County. The

District’s levy amount for fiscal year 2009 is approximately $49.9 million, a 7.8 percent

increase from fiscal year 2008, which was the maximum allowable levy limit

calculated by the County Assessor.

Federal and state assistance

As shown in Table 4 (see page 16), federal and state assistance revenues have

increased from $22.3 million in fiscal year 2006 to $45 million in fiscal year 2008, an

increase of about $22.7 million or about 102 percent, during that time period.

2

Most

of these revenues are reimbursements provided to cover the costs of services for

various state or federal programs described below. Specifically:

GGrraadduuaattee

MMeeddiiccaall

EEdduuccaattiioonn

((GGMMEE))——

This federal program, which requires a

state match, recognizes that teaching hospitals incur significant costs, such as

residents’ salaries, employee benefits, and training costs, in addition to the costs

associated with patient care. AHCCCS is responsible for allocating the federal

and state matching monies annually among the Arizona hospitals according to

statutory and administrative code requirements.

3

The District’s GME revenue has increased by approximately $13.2 million, or 144

percent, since fiscal year 2006. According to a district official, its payment has

significantly increased because AHCCCS allocated monies to compensate for

its uncompensated indirect program costs incurred for training the residents in

fiscal year 2008.

4

Prior to fiscal year 2008, the District received allocations only

for uncompensated direct program costs for training the residents. According to

1

Maricopa County transferred the system’s fiscal and operational responsibilities to the District on January 1, 2005. The

District’s first property tax was levied in August 2005 in accordance with Arizona Revised Statutes §§42-17151 and 48-

5563.

2

In Table 4 (see page 16), the sum of the “other” category represents less than 1 percent of the District’s total revenues.

Thus, auditors do not describe it in this chapter.

3

Arizona Administrative Code, Title 9, Chapter 22, Article 7.

4

The GME program recognizes that a hospital may experience a marginal increase in its operating costs. Therefore, the

federal government has established a formula for calculating an indirect cost amount that is based on a hospital’s

residents-to-beds ratio and a congressionally approved rate.

Property Tax

Fiscal Years 2006 through 2008

(Unaudited)

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial

statements and general ledgers for fiscal years 2006 through

2008.

2006 2007 2008

$40,000,000 $43,000,000 $46,310,880

a district official, in fiscal year 2009, the District expects to receive approximately

the same GME amount as in fiscal year 2008.

MMeeddiiccaaiidd

DDiisspprrooppoorrttiioonnaattee

SShhaarree

HHoossppiittaall

((DDSSHH))

PPaayymmeennttss——

Under this

program, the federal government reimburses states for a portion of the medical

services costs that their hospitals incur when providing care to people they do

not expect to receive payment from. Such costs are known as uncompensated

care costs (see Chapter 6, pages 55 through 63, for additional information).

AHCCCS is responsible for allocating these monies annually to the State and

qualifying Arizona hospitals. The District has received approximately $4.2 million

in DSH monies each fiscal year since its inception. In January 2009, the

Legislature eliminated the District’s share of DSH monies for fiscal year 2009.

1

FFeeddeerraallllyy

QQuuaalliiffiieedd

HHeeaalltthh

CCeenntteerrss

((FFQQHHCC))——

This federal program, which

requires state matching monies, provides the District with additional payments

when AHCCCS members obtain services at district community centers that

have been certified as federally qualified healthcare center look-alikes.

2

According to the District, it pursued the FQHC designation as an important step

in allowing the District to expand services throughout the community and was

awarded this designation in 2006. AHCCCS is required to reimburse the District

State of Arizona

page 16

1

Laws 2009, 1st S.S., Ch. 4, §7.

2

A federally qualified health center (FQHC) is a type of provider defined by the Medicare and Medicaid statutes. FQHCs

include all organizations receiving grants under Section 330 of the Public Health Service (PHS) Act, certain tribal

organizations, and FQHC Look-Alikes. An FQHC Look-Alike is an organization that meets all of the eligibility requirements

of an organization that receives a PHS Section 330 grant, but does not receive grant funding.

2005

(6 months)

2006 2007

2008

Graduate medical education $ 9,177,507 $10,528,218

$22,394,965

Medicaid disproportionate share

hospital payments $2,101,144 4,202,300 4,202,300

4,202,300

Federally qualified health

centers 1,290,675 3,625,649

7,364,685

Ryan White grants 1,471,282 2,980,845 3,178,687

3,524,278

Arizona primary care program 1,035,401 1,804,010 2,473,706

2,668,146

Trauma and emergency services 896,833 2,377,933 3,000,441

3,630,129

Other

2

237,996 449,922 1,403,316

1,262,192

Total federal and state

assistance $5,742,656

$22,283,192 $28,412,317

$45,046,695

Table 4: Schedule of Federal and State Assistance

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

1

(Unaudited)

1

Maricopa County transferred the system’s fiscal and operational responsibilities to the District on January 1, 2005, and therefore,

fiscal year 2005 amounts represent activity for only 6 months.

2

Consists of tobacco use prevention, hospital preparedness-bioterrorism, health academy, transportation-related injury prevention,

newborn intensive care, and other program revenues.

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial statements and general ledgers for the 6-month period ended

June 30, 2005, and for fiscal years 2006 through 2008.

Office of the Auditor General

page 17

quarterly for the difference between the FQHC rate and the AHCCCS rate for the

Medicaid patients who visited the District’s community health centers. The

District began receiving the FQHC reimbursements from AHCCCS in March

2006.

The District’s share of FQHC revenue has increased by $6.1 million, or nearly

471 percent, since fiscal year 2006. According to district budget documents and

AHCCCS staff, the increase resulted from about a 20 percent in increase in clinic

visits and a nearly 43 percent FQHC rate increase since March 2006. The District

received a significant rate increase in October 2007 because AHCCCS adjusts

the FQHC rate every third federal fiscal year. For fiscal year 2009, AHCCCS

expects to reimburse the District approximately $7 million.

RRyyaann WWhhiittee GGrraannttss——

The Ryan White Human Immunodeficiency Virus or

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) grants are for programs that

provide HIV-related health services. These federal grant monies are to be used

for those who do not have sufficient healthcare coverage or financial resources

for coping with HIV. The District annually applies for these federal grants, which

must be used to provide outpatient services including primary care, dental,

mental health, and substance abuse services for HIV patients. The annual

contract award amount is based on the amount budgeted at the federal level for

these grants.

The District’s Ryan White grants have increased by over $500,000, or

approximately 18 percent, since fiscal year 2006. According to the District, the

primary reason for the increase is that more federal funding was available in

fiscal years 2007 and 2008. According to district budget documents, for fiscal

year 2009, the District expects the Ryan White grants to increase by nearly 1

percent.

AArriizzoonnaa

PPrriimmaarryy

CCaarree

PPrrooggrraamm——

This program offers comprehensive primary

care and preventive dental services to uninsured residents of Arizona whose

family income is below 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines and who

are not eligible for Medicare or AHCCCS. This program is funded by the State

General Fund and tobacco tax monies. Using a competitive bidding process,

the Arizona Department of Health Services awarded a contract to the District that

began in July 2005 with options to renew each year for a maximum of 4 years.

The annual contract award amount is based on the amount budgeted at the

state level for this program. The District submits expenditure and other data

monthly to the Arizona Department of Health Services for reimbursement.

The District’s revenue for this program has increased by almost $900,000, or

nearly 48 percent, since fiscal year 2006. According to a district official, the

primary reason for the increase is that the State budgeted more funding for this

program in fiscal years 2007 and 2008. For fiscal year 2009, the Department of

Health Services renewed its contract with the District for $2.8 million, almost a 5

percent increase from fiscal year 2008.

TTrraauummaa

aanndd

EEmmeerrggeennccyy

SSeerrvviicceess

—These revenues, which come from a portion

of Indian gaming revenues, help to cover a portion of the unrecovered trauma

and emergency services costs incurred by qualified trauma centers in the

State.

1

The District’s hospital is one of seven trauma centers in Arizona.

According to administrative code requirements, AHCCCS is responsible for

allocating these monies biannually among the State’s trauma centers based on

the reported number of trauma cases and the related unrecovered trauma and

emergency costs.

2

The District’s share of the trauma and emergency services payment has

increased by about $1.3 million, or nearly 53 percent, since fiscal year 2006.

According to district budget documents, the increase is attributable to better

reporting of eligible expenses to AHCCCS. The District expects its fiscal year

2009 revenue from this source to remain nearly the same as fiscal year 2008.

County assistance

As shown in Table 5, the District has received assistance from Maricopa County since

fiscal year 2005. These revenues subsidize the District’s psychiatric residency

teaching program and stabilize the District’s financial position during the transition

period.

State of Arizona

page 18

2005

(6 months)

2006

2007

2008

Psychiatric residency teaching program $1,773,948 $3,547,900 $3,547,896 $3,547,896

Assistance package 1,618,771

4,446,768 767,976 817,126

Total county assistance $3,392,719

$7,994,668 $4,315,872 $4,365,022

Table 5: Schedule of Maricopa County Assistance

Fiscal Years 2005 through 2008

1

(Unaudited)

1

Maricopa County transferred the system’s fiscal and operational responsibilities to the District on January 1, 2005,

and therefore, fiscal year 2005 amounts represent activity for only 6 months.

Source: Auditor General staff analysis of the District’s audited financial statements and general ledgers for the 6-month

period ended June 30, 2005, and for fiscal years 2006 through 2008.

1

During the November 2002 election, voters approved Proposition 202, which allowed casinos to increase the numbers

of slot machines and gaming tables, such as blackjack, in exchange for the State’s receiving 1 to 8 percent of their

revenue. A portion of that revenue is used to fund the trauma and emergency services program.

2

Arizona Administrative Code, Title 9, Chapter 22, Article 21.

Office of the Auditor General

page 19

Specifically, these revenues subsidize the following:

PPssyycchhiiaattrriicc

RReessiiddeennccyy

TTeeaacchhiinngg

PPrrooggrraamm——

The 1989 Arizona Supreme Court

ruling in the Arnold v. Sarn case granted class action status to indigent seriously

mentally ill people and ruled that both the State and Maricopa County had failed

to provide adequate services and funding to this population in Maricopa

County.

1

According to Maricopa County, in 1993 the court monitor assigned to

assess compliance with the ruling determined that Maricopa County should

continue to provide at least the same level of service to class members through

the psychiatric residency teaching program as it provided in fiscal year 1993. As

a result, since the District’s inception, Maricopa County has provided

approximately $3.5 million each fiscal year for the District’s psychiatric residency

teaching program. For fiscal year 2009, according to Maricopa County budget

documents, the County budgeted the same amount for the program.

AAssssiissttaannccee

PPaacckkaaggee——

In June 2005, the District accepted the assistance

package offered by Maricopa County’s Board of Supervisors. According to this

package, it serves as a means to stabilize the District’s financial position. It

includes:

• Two waivers, one for approximately $1.6 million in election costs for the first

election that created the District, and one for $1.1 million in rental payments

for the Comprehensive Health Care Center.

• $2.6 million in cash assistance to pay for consulting services.

• Two loans—one for a $15 million line of credit and one for $443,000 in

election costs for the second election that created the District’s Board of

Directors. These 10-year loans are interest-free for the first 5 years.

The District recognized the election, consulting services, and rental assistance

as revenues in fiscal years 2005 and 2006. The waiver of interest expense is

being reported as revenue over the 5-year, interest-free period and will expire in

fiscal year 2011.

1

Arnold v. Sarn, 160 Ariz. 593, 775 P.2d 521 (1989).

State of Arizona

page 20

Financial stability

The Maricopa County Special Health Care District’s (District) financial

stability has generally improved, but the District’s plans for a new hospital

highlight the need for it to take additional steps to ensure future stability.

When the District inherited the Maricopa Integrated Health System

(System) from Maricopa County (County), the System’s financial condition was weak.

Various financial indicators show that the District’s financial condition has since

improved, though there are still reasons for concern. The District has taken

preliminary steps to plan for a new hospital and improve its clinics—actions that, if

carried out, may require the District to borrow substantially. Taking steps such as

developing strategies for modifying projects and limiting risks, as well as continuing

various financial stability initiatives already underway, will help the District as it

prepares to address its future needs.

District has shown signs of improved financial stability

Since the District took over the System’s operation from the County, the District has

shown signs of improved financial stability. Reports from the County indicate that the

System was facing a financial crisis before transitioning to the District in January

2005. Since then, the District’s audited financial statements and related financial

indicators have shown signs of improvement, such as total net assets almost

doubling from June 2005 to June 2008. However, other measures of financial stability

point to ongoing concerns—the District reported that its financial condition is not yet

strong enough to obtain an investment-grade bond rating, has significant bad debt

and charity care expenses, and has older facilities.

System in poor financial condition when transferred to District—Right

before its transition from the County to the District, the System was in poor financial

condition. According to a citizens’ task force established in 2003 by the County’s

Board of Supervisors and a 2004 financial condition report by the County’s Internal

Audit Department, the System was facing a financial crisis. Reasons for this crisis