Made possible with support from Blue Shield of California Foundation and the California Health Care Foundation.

BRIEF | JULY 2019

Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed

Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and

Behavioral Health

By Logan Kelly, Michelle Conway,

*

and Michelle Herman Soper, Center for Health Care Strategies

IN BRIEF

Clinical integration of physical and behavioral health services may improve health outcomes and reduce costs for

individuals with behavioral health conditions, but separate Medicaid financing for physical and behavioral health

care can create barriers to coordinated care delivery. In recent years, several states have begun contracting with

comprehensive managed care plans to integrate behavioral health services and reduce the fragmentation of care

for Medicaid enrollees. This brief, produced with support from Blue Shield of California Foundation and the

California Health Care Foundation, describes how integrated financing influences the coordination of physical and

behavioral health services at the care delivery or practice level. It distills insights from providers in three states —

Arizona, New York, and Washington — that have recently transitioned to integrated managed care. Based on their

insights, the brief highlights recommendations for states seeking to improve health outcomes through advancing

greater physical-behavioral health integration organized within three key areas: (1) data and quality measures; (2)

payment and business practices; and (3) integrated clinical service delivery.

Background

Health Impacts and Costs of Behavioral Health Conditions

People with behavioral health conditions — those with mental health and/or substance use

disorders (SUD) — are more likely to experience poor health and social outcomes as well as high

costs of care.

1

They have higher rates of chronic physical conditions, as well as increased rates of

homelessness, unemployment, poor educational performance, and involvement with the criminal

justice system.

2

Strikingly, people with serious mental illness (SMI) die on average 25 years earlier

than those without SMI.

3

Medicaid is the single largest payer for behavioral health services in the United States, with nearly 20

percent of Medicaid enrollees having a behavioral health diagnosis.

4

Medicaid spending for

enrollees with behavioral health conditions is more than four times higher than those without these

conditions, largely as the result of increased physical health care spending.

5

One study found that

over 80 percent of the increased costs for people with comorbid mental and physical health

conditions were associated with physical health expenditures.

6

*

Michelle Conway is a former intern at the Center for Health Care Strategies.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 2

Despite the connections between behavioral and physical health conditions, many Medicaid

enrollees experience gaps in care due to the lack of coordination and information sharing between

medical and behavioral health providers, which can result in adverse outcomes for patients with

comorbid conditions. People with behavioral health conditions also tend to receive less preventive

care and lower-quality physical health care, a disparity that may be affected by the stigma associated

with behavioral health conditions.

7

Physical-Behavioral Health Integration

Many physical and behavioral health providers say that integrated care better meets the needs of

patients with multiple co-occurring conditions. Integrated behavioral health care (integrated care) is

defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as: “the care a patient experiences as a

result of a team of primary care and behavioral health clinicians, working together with patients and

families, using a systematic and cost-effective approach to provide patient-centered care for a

defined population. This care may address mental health and substance abuse conditions, health

behaviors (including their contribution to chronic medical illnesses), life stressors and crises, stress-

related physical symptoms, and ineffective patterns of health care utilization.”

8

Clinical integration references processes to advance integrated care at the point of service delivery,

and is often represented as a continuum beginning with coordinated care and then co-located care,

with the highest level defined as full collaboration in a transformed/merged integrated practice.

9

While clinical integration can be implemented in different settings that serve different populations,

integration of behavioral health into primary care settings most frequently targets people with mild

to moderate mental health conditions. Integration of primary care into behavioral health settings

targets adults with SMI and SUD and children with serious emotional disturbances (SED) who may

have high levels of physical health comorbidities. There is growing evidence that clinical integration

can improve health outcomes and quality of life as well as reduce health care costs.

10

Many states

have initiated efforts to pursue clinical integration, especially for vulnerable populations of high-need

Medicaid enrollees.

11

One barrier states face in advancing clinical integration for Medicaid enrollees is separate financing

structures for physical and behavioral health care. For many years, most states with Medicaid

managed care programs have “carved-out” behavioral health benefits from physical health benefits.

While the majority of states organize and finance physical health benefits through comprehensive

managed care organizations (MCOs), mental health and SUD services have been administered by

separate managed behavioral health organizations (which are often public entities) or on a fee-for-

service basis. Under such systems with a person’s care managed by multiple entities, consumer

access to care and care coordination can be diminished, resulting in worse health outcomes.

12

In recent years, several states have transitioned to integrated financing models by contracting with

integrated managed care plans that manage all physical and behavioral health services for Medicaid

enrollees, to decrease fragmentation of care, improve health outcomes, and reduce costs. A primary

goal of these programs is to enhance providers’ access to data, incentives, and tools to deliver

integrated services and coordinate care across settings. The potential of integrated physical-

behavioral health financing to improve care and outcomes hinges on whether the integration of

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 3

financing supports integration at the clinical level, and whether consumers — particularly those with

complex health and social needs — receive care that is better coordinated.

To examine whether integrated financing is delivering on the promise of improved clinical

integration and coordination at the practice level, the Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS), with

support from Blue Shield of California Foundation and the California Health Care Foundation,

conducted interviews with leaders of nine provider organizations in three states — Arizona, New

York, and Washington — that have implemented integrated Medicaid managed care programs.

Most interviewees reported that their state’s movement toward plan-level financial integration has

accelerated their organization’s clinical integration progress. Providers identified three key levers for

successfully advancing integrated care that are described in this brief:

1. Integrated data-sharing and quality measures to use with plans and providers;

2. Payment and business practices that align financial incentives for providers to deliver

integrated care, including adoption of value-based payment arrangements; and

3. Integration in clinical service delivery, including adoption of clinical practices that foster

integrated care delivery, such as service redesign, assessments, staffing, and care planning.

Whereas the overall feedback from interviewees highlights the promise of financial integration,

many providers also identified challenges and unintended consequences resulting from the design

and implementation of state transitions to integrated financing. This brief shares insights from both

positive and negative experiences that can inform future state efforts to advance clinical integration.

Recommendations for other states seeking to advance integration follow each of the three thematic

sections. These recommendations identify critical decisions for states related to both the design of

integration policies and the transitions to and ongoing monitoring of integrated managed care

programs.

Profiled States and Providers

This brief draws on interviews with providers in Arizona, New York, and Washington. These states

were selected based on their recent and diverse approaches, as summarized below, to implementing

integrated managed care. (See Appendix 1 for additional details about each state’s transition,

including a timeline and description of how providers were paid during each phase.)

Arizona

In 2013, Arizona’s state Medicaid agency, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System

(AHCCCS), began integrating the financing of physical and behavioral health services for certain

populations. Before 2013, MCOs were primarily responsible for physical health services, while most

Medicaid behavioral health services were carved out of AHCCCS Medicaid MCO contracts, and

separately managed by Regional Behavioral Health Authorities (RBHAs). Through a geographically

phased rollout that launched in 2014, newly integrated RBHAs began managing physical and

behavioral health services for adult Medicaid enrollees with SMI. In 2018, integrated AHCCCS

Complete Care (ACC) plans began managing both physical and behavioral health services for enrollee

populations that previously enrolled in separate plans, including: (1) children with SED; (2) adults

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 4

with SUD; and (3) adults and children with mild-to-moderate behavioral health needs. An evaluation

of 2013-2014 integration initiatives found improvement in all measures of patient experience,

ambulatory care, preventive care, and chronic disease management. Hospital-related measure

results were mixed, however. While the majority of these measures, such as 30-day post-

hospitalization for mental illness follow up rate, showed improvement, some measures such as

inpatient utilization rate showed a performance decline.

13

New York

Prior to 2015, most specialty behavioral health services in New York were carved out of managed

care plans and provided via fee-for-service. In 2015, New York began transitioning all adults eligible

for Medicaid managed care to receive physical and behavioral health benefits from an integrated

managed care plan, and created a new type of health plan, called a Health and Recovery Plan

(HARP). HARPs are separate products within existing MCOs for adults with SMI and serious SUD

diagnoses, and have additional requirements for care management and newly added home- and

community-based services benefits. New York is phasing in integrated managed care plans and

HARPs for children in 2019, along with expanding covered mental health and SUD services for

children and their families. New York issued a request for proposals in January 2019 to evaluate this

behavioral health demonstration, including improvements in health and behavioral health outcomes

for enrollees in integrated MCOs.

14

Washington

Before 2016, three separate entities managed physical and behavioral health care in Washington:

(1) all physical health as well as behavioral health services for individuals with mild to moderate

needs were managed by MCOs; (2) specialty mental health services for enrollees with SMI were

managed by Regional Support Networks (RSNs) that subcontracted with community mental health

agencies to deliver care; and (3) SUD services were administered through multiple regional and state

contracting mechanisms. In 2016, the Washington Health Care Authority (HCA) began implementing

fully integrated managed care, phased in by region. Under the fully integrated managed care model,

MCOs provide physical and behavioral health services to adults and children, while the state

contracts with administrative service organizations in every region to deliver crisis services to

Medicaid and non-Medicaid enrollees. An evaluation of integration efforts for adult populations in

an early adopting region found statistically significant improvement in 10 out of 19 enrollee

outcomes in 2016 and 11 out of 19 enrollee outcomes in 2017, including access to preventive/

ambulatory health services, SUD treatment penetration, and mental health treatment penetration.

15

Most other outcomes did not show significant relative change, though two outcomes

(comprehensive diabetes care — hemoglobin A1C testing and emergency department (ED)

utilization per 1,000 coverage months) showed statistically significant unfavorable changes. Notably,

the unfavorable change in ED utilization in the early adopting region was measured in comparison

with the rate of decreased utilization in other regions, which had higher historical rates of utilization.

Interviewed Providers

In each state, senior Medicaid and behavioral health officials identified and assisted in recruiting

interviewees from among provider organizations who collectively have sought to advance clinical

integration across various settings and an array of subpopulations. The profiled organizations, as a

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 5

result, include many leading-edge providers with valuable insights on the lessons, challenges, and

benefits of clinical integration, though this group is not representative of the full range of provider

experiences related to transitioning to integrated financing models.

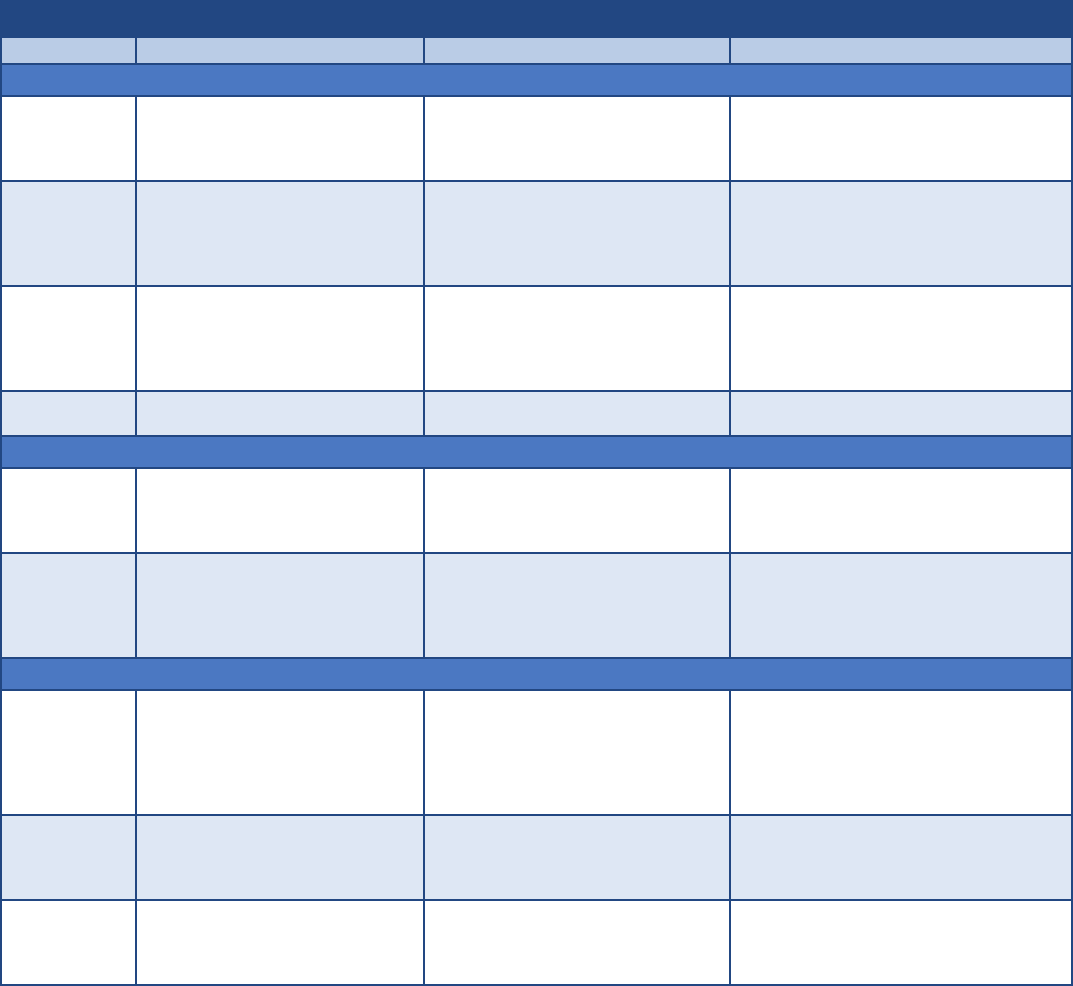

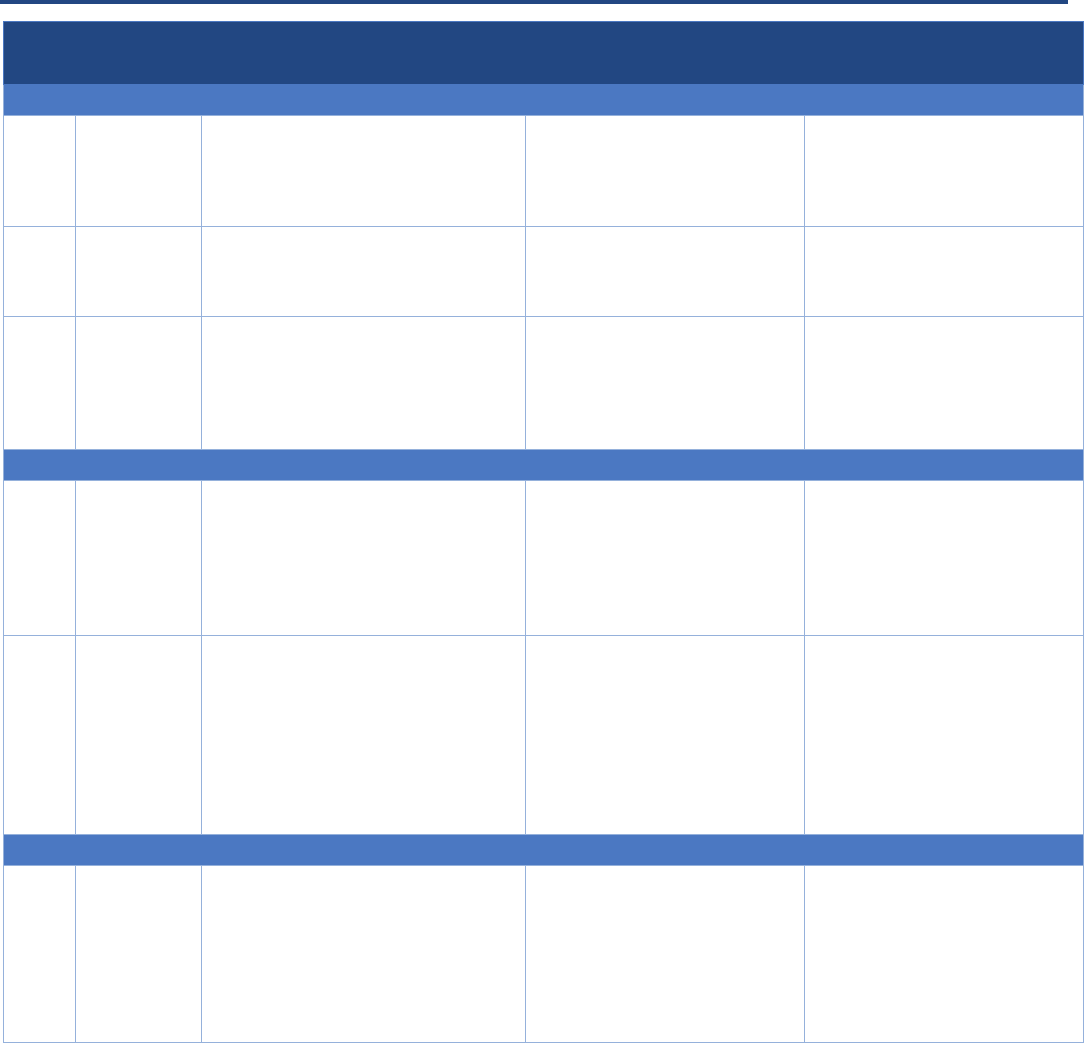

As summarized in Table 1, the interviewed providers had different lengths of experience working

with integrated managed care plans ranging from six weeks to six years, and included providers

serving adults and children and delivering an array of primary care, mental health, and SUD services.

Table 1. Interviewed Providers

Provider

Population Served

Services Provided

Transition(s) to Integrated Managed Care

ARIZONA

Children’s

Clinics

More than 5,000 children with

complex chronic diagnoses, primarily

children with Children’s Rehabilitative

Services (CRS) conditions

16

Primary and mental health care for

families, rehabilitative therapies,

pediatric specialty care, and

multidisciplinary clinics

2013. CRS members began receiving services

managed by one statewide integrated CRS

plan; as of 2018, services for CRS members

are managed by integrated ACC plans

Partners in

Recovery

More than 8,000 adults with SMI

Mental health services including

assertive community treatment (ACT),

psychosocial rehabilitation/peer

services, primary care, and health and

wellness services

2014. Members with SMI began receiving

services managed by integrated RBHA

Bayless

Integrated

Healthcare

More than 20,000 adults and children

for primary care including children

with mild to severe behavioral health

needs and adults with mild to

moderate behavioral health needs

Behavioral health services including

substance use, primary care, and

school-based physical and behavioral

services

2018. Adults and children received services

from integrated ACC plans; previously, adults

and children received behavioral health

services through a RBHA while and physical

health services through another MCO

Happy Kids

Pediatrics

More than 40,000 children

Primary care

2018. Most children began receiving services

managed by integrated ACC plans

NEW YORK

Institute for

Community

Living (ICL)

More than 10,000 adults and

children, including individuals with

mental illness and intellectual and

developmental disabilities

Mental health, supportive services, and

service-enriched housing*

2015. New York City region transitioned to

integrated MCOs and HARPs

Access:

Supports for

Living

More than 8,000 children and

families with mental illness,

substance use disorders, and/or

intellectual or developmental

disabilities

Behavioral health services (including all

Certified Community Behavioral Health

Clinics services), care management,

supportive services, and service-

enriched housing*

2016. New York State (non-New York City)

transitioned to integrated MCOs and HARPs

WASHINGTON

Clark County

Community

Services

As a county government agency,

serve the more than 465,000

residents of Clark County

Funder of non-Medicaid mental health

and SUD services, housing and

homeless services, permanent

supportive housing, and other services;

directly manage crisis responder

services

April 2016. Region transitioned to fully

integrated managed care

Catholic

Charities of

Central

Washington

More than 3,000 children and adults

Counseling and behavioral health

services, family support services, early

learning and child services, and

affordable housing*

January 2018. The North Central region

transitioned to fully integrated managed care

Mid-Valley

Clinic

Children and adults

Multispecialty clinic certified as rural

health clinic delivering primary,

specialty, and surgical care as well as

behavioral health services

January 2019. County transitioned to fully

integrated managed care

* Also partners with a federally qualified health center to deliver integrated physical and behavioral health care in at least one

clinical setting.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 6

Provider Insights on the Impact of Integrated Managed Care

on Clinical Integration

All nine interviewed providers have embraced new opportunities to better integrate care in their

clinical settings to more effectively serve patients with physical and behavioral health needs. Many

interviewees said their state’s transition to integrated financing facilitated provider-level data-

sharing, quality measures, and aligned financial incentives. Those improvements accelerated clinical

integration and care coordination; however, the extent of this acceleration depended on a wide

range of factors, including the state’s approach to integration, the underlying managed care and

policy environments, and characteristics of the local delivery system.

Following is a discussion of three levers that are critical for driving clinical integration in new

financially integrated programs: (1) integrated data-sharing and quality measures; (2) payment and

business practices, and (3) integrated clinical service delivery. Each section includes examples of

strategies that promote integration; as well as challenges that need to be addressed to fully embrace

these changes in new integrated models. Finally, each section concludes with several policy

recommendations for states to consider as they design and implement integrated programs.

1. Integrated Data-Sharing and Quality Measures

Financial integration creates a lever for plans and providers to share more comprehensive data

about patients’ physical and behavioral health diagnoses, utilization, referrals, and treatment plans,

because health plans now have access to data across a broader continuum of services. Providers can

use integrated data to better understand the array of patient needs; assess the gaps in care

;

coordinate treatment plans; identify high-cost, high-need patients; and develop targeted quality

improvement activities. Plans can use comprehensive data from providers to support providers’

activities to better coordinate and close gaps in care as well as to develop and refine performance

measures and financial incentives. However, while all providers interviewed spoke about the

importance of bidirectional exchange of data to better manage consumer needs, the extent to which

providers’ access to data increased after a transition to integrated managed care varied. Factors that

improved providers’ access to and use of data include: (1) partnerships and infrastructure that

enable information-sharing with managed care plans; (2) investments in health information

exchanges; and (3) plan-provider collaboration on developing integrated quality measures to enable

greater accountability for performance.

Data-Sharing with Integrated Managed Care Plans

Some behavioral health providers said that the transition to integrated financing had a rapid and

game-changing impact on data-sharing, noting that they began receiving data from plans and thus

could more effectively identify and engage high-need patients. In Arizona, leadership at Partners in

Recovery said that in the previous system of carved-out behavioral health services, providers had

limited access to physical health data, and thus, “we were blind to half of the conditions that our

patients have.” Following the transition to integrated RBHA plans for adults with SMI, Partners in

Recovery immediately began receiving primary and acute care utilization data. These data

uncovered, for example, that one Partners in Recovery patient had visited the ED 96 times in the

past year, with 24 inpatient admissions — and that Partners in Recovery providers had never known

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 7

about these visits. Now, Partners in Recovery can identify and engage patients at high risk for acute

care utilization to find alternatives to visiting the ED. Similarly, Catholic Charities in Washington

began receiving extensive encounter data following the transition to fully integrated managed care,

including from local jails that shared data with integrated MCOs. Catholic Charities can now

proactively engage patients with behavioral health conditions such as SUDs immediately after law

enforcement encounters.

The experience of real-time data-sharing was not universal, however. Some providers in states that

had transitioned to integrated care within the last six months observed that newly integrated plans

may require additional time to understand behavioral health services before they can more

effectively organize and analyze data for bidirectional data-sharing with providers. There may be

system incompatibilities too. Behavioral health providers are generally less likely than physical health

providers to have or use health information technology. Among those who do use this technology,

managed care plan data systems may not be compatible with behavioral health providers’ electronic

health records (EHRs). Additionally, physical and behavioral health providers may need to redesign

their EHR not only to incorporate new data inputs across multiple provider types, but also to

highlight the specific elements most relevant for different provider types and protect sensitive data

in accordance with federal and state confidentiality regulations. Providers agreed that investments

from plans and providers will be critical to future improve data-sharing capabilities.

Most interviewed behavioral health providers experienced an increase in the number of entities that

pay for services as a result of the transition to integrated managed care, which has consequences for

data-sharing. Working with a single or small number of integrated plans, as opposed to a large

number, may offer opportunities to improve data-sharing through closer plan-provider

collaboration. In Arizona, Partners in Recovery works primarily with one integrated RBHA. These two

organizations partnered to develop a population health platform using comprehensive clinical and

claims data, allowing Partners in Recovery to “accelerate the use of data for care management in

ways that were unimaginable before an integrated RBHA.” On the other end of the continuum, a

provider working with more than 10 different MCOs in another state described significant challenges

in receiving and working with data across all entities, especially when consumers frequently change

plans. As a result, this provider is reliant on older claims data, limiting effectiveness to inform

interventions.

Leveraging Health Information Exchanges

Providers reported multiple benefits of participating in information-sharing through a state

electronic health information exchange (HIE), and highlighted the importance of real-time hospital

data alerts to better identify and engage high-risk patients. In 2016, all three of Arizona’s integrated

RBHAs invested in a statewide plan to integrate physical and behavioral health data in the HIE, which

also exempts behavioral health providers from participation fees.

17

The state has reported significant

increases in behavioral health provider participation in this HIE.

18

In Arizona, when Partners in

Recovery providers receive an HIE alert that a patient has visited a hospital, they immediately

communicate with that hospital to understand the underlying reasons for the visit and intervene, if

necessary, to help the patient access care in the most appropriate setting. In New York, the

statewide HIE connects regional health information organizations to store and share electronic

health data.

19

Access: Supports for Living (Access) in New York is an early adopter of the regional HIE

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 8

and can pull real-time utilization data to target patient outreach. Each morning, Access receives an

email listing of all patients who presented at a hospital the previous evening, and clinical leaders

then participate in a morning huddle to discuss these patients and develop strategies for follow-up

care to prevent readmissions. Additionally, the HIE allows Access to see data on recent inpatient

discharges and the New York State Office of Mental Health database provides data on quality

measures, so staff can focus on engaging patients at risk for gaps in care. For example, staff now use

these systems to proactively engage individuals who are prescribed anti-psychotics and have not

received clinical testing for diabetes.

Quality Measures

Increased data-sharing can improve accountability

for provider performance. Providers, often in

collaboration with integrated plans, are using new

approaches to evaluate consumer outcomes across

physical and behavioral health domains and across

different service lines. For leaders at Access in New

York, using Healthcare Effectiveness Data and

Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures to

understand the impact of the behavioral health

services they provide on physical health outcomes

served as a “real awakening for us to think about

whole health care, and changed how we measured

our outcomes.” Leadership at Bayless Integrated

Healthcare in Arizona described using HEDIS

measures to assess the effectiveness of different

evidence-based mental health treatment practices

for patients with co-occurring conditions.

Increased access to data can also support the

design of clinical processes that may improve

consumer health and quality of life outcomes. While managed care plans have a long history of using

a robust set of physical health data to assess the quality of physical health services and measure

outcomes, they may have a steep learning curve in understanding how behavioral health services —

and integrated care — can affect both physical and behavioral health outcomes. In newly integrated

systems, providers can leverage robust data on physical and behavioral health to build more

effective partnerships with plans and capture the interconnectedness of physical and behavioral

health in care models.

Using Quality Measures to Drive Integrated Care

For Catholic Charities

in Washington State,

the transition to fully

integrated managed

care led to a focus on

developing a new

“whole person care data set” designed to track outcomes

related to integrated health care. This data set includes

relevant measures related to physical and behavioral health

conditions as well as social determinants of health (SDOH)

and patient activation measures (PAM) to assess self-care

and advocacy. Catholic Charities plans to work with its

integrated MCOs to incorporate HEDIS measures into this

data set, and use its performance on these quality measures

in negotiating risk contracts.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 9

Data and Quality Measures: Policy Recommendations for States

Access to integrated physical and behavioral health data is critical for providers to effectively meet the needs of

patients with co-occurring conditions. Interviewees offered many insights on how to most effectively leverage newly

available data from integrated managed care plans as well as from other providers to improve the clinical delivery of

care. Additionally, many noted that their abilities as providers to access and analyze integrated data, and to be

assessed on specific quality measures, will help integrated plans more effectively understand the impact of

behavioral health services on health outcomes and improve value-based payment reforms for behavioral health

providers. Following are data and quality measure recommendations for states to consider in designing and

implementing integrated managed care:

1. Facilitate the development of robust data-sharing protocols between integrated plans and providers prior to the

launch of integrated plans.

2. Invest in behavioral health provider readiness on data-sharing and interoperability, including design and

adoption of electronic health record systems for integrated care.

3. Invest in electronic health information exchange across medical, behavioral health, and acute care providers to

enable all providers to most effectively coordinate and reduce gaps in care.

4. Consider the impact of the number of integrated plans on provider data-sharing and ability to be held

accountable for patient outcomes.

5. Develop a quality measure set, with stakeholder input, including process and outcomes measures that

collectively assess accountability for meaningful outcomes for individuals with physical and behavioral health

needs. These measures should be included in integrated managed care plan contracts as appropriate.

2. Payment and Business Practices

With the appropriate financial, infrastructure (such as billing, data collection and reporting, and

information technology), and human resource supports in place to adopt new payment and business

models, payment levers can accelerate providers’ capacity to deliver integrated care. While not all

state transitions to integrated financing models included changes to provider payment structures at

the outset, integrated financing can better align system incentives to deliver integrated care and

promote provider accountability for managing a more complete range of services. Interviewees

noted that following transitions to integrated care, many pursued different business practices, such

as participating in state incentive programs, implementing value-based payment (VBP)

arrangements, and developing new business relationships. Finally, many providers identified

opportunities for states to mitigate administrative burden related to the transition to integrated

managed care, which may be particularly relevant for behavioral health providers that have not

previously worked with managed care.

Incentive Programs and Value-Based Payment Arrangements

Interviewees described the transformative potential of new payment models, including state

incentive programs and value-based contracts, to support their efforts to improve health outcomes

through clinical integration. AHCCCS launched the Targeted Investments Program through a 2017

amendment to Arizona’s section 1115 demonstration beginning in 2016, and invested $300 million

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 10

to support both physical and behavioral health providers in developing the infrastructure for

integrated care.

20

Participating providers receive incentive payments annually, contingent on

meeting milestones applicable to their provider type. (See Appendix 2 for additional information

about Targeted Investments provider eligibility requirements, milestones, and payments.)

Interviewees said this program effectively incentivizes communication protocols between medical

and behavioral health providers and care coordination for high-risk patients. Physical and behavioral

health providers work toward different milestones, but also have opportunities to work together to

improve care and receive incentive payments. Providers highlighted the importance of collaborating

to define high-risk patients and identify areas of clinical overlap where both types of providers could

improve care.

In other states, even where state policy has largely maintained existing payment structures,

partnerships with integrated managed care plans are allowing some behavioral health providers to

begin participating in VBP arrangements that incentivize clinical integration. For example, although

the transition to integrated care continued the underlying fee-for-service payment system for

behavioral health provider payments, New York concurrently rolled out an extensive VBP initiative

that included a number of voluntary opportunities to promote incentives and accountability for

integrated care.

21

Access participates in Coordinated Behavioral Health Services, a behavioral health

independent practice association (IPA) focused on integrated behavioral and physical health. It also

holds a value-based contract with an integrated MCO that will shift later this year to an arrangement

with both upside and downside risk. Also in New York, Institute for Community Living has partnered

with Healthfirst (an MCO that offers a HARP plan) in a HARP VBP pilot.

22

Representatives of both

providers said that they have improved health outcomes and are better-prepared to participate in

future VBP arrangements because of their participation in these arrangements.

Other providers have worked closely with their integrated managed care plans, and in some cases

with their state Medicaid agency, to develop and refine VBP arrangements that advance integrated

physical and behavioral health services. Plans may also be able to make investments in critical

capacity areas that allow providers to meet requirements for new payment models, such as

information technology, and data collection and reporting capacity. Bayless Integrated Healthcare in

Arizona has value-based contracts with most ACC plans, and has worked closely with these plans to

educate them about behavioral health care models, payment rates, and coding practices, among

other things, to develop financially sustainable contract terms. Similarly, Children’s Clinics in Arizona

has collaborated with plans and AHCCCS to develop behavioral health quality measures for VBP

models. As part of this effort, Children’s Clinics negotiated a wraparound rate for key behavioral

health services that were not previously reimbursable. Similarly, Partners in Recovery in Arizona

receives incentive payments from its partner RBHA based on physical health performance measures

such as increasing the number of patients with diabetes who receive an annual retinal eye exam. To

achieve this objective, Partners in Recovery now works with a local optometrist and coordinates

appointments for their clients within their clinics.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 11

New Business Relationships

Adoption of new integrated financing models can drive physical and behavioral health providers to

explore new partnerships. In 2018, Arizona’s Happy Kids Pediatrics began working with integrated

ACC plans in 2018, and also established a partnership with a behavioral health provider to offer co-

located physical and behavioral health services to more effectively meet the behavioral health needs

of its patient population. The potential for incentive payments from the Targeted Investments

Program strengthened the business case for this new collaboration. For pediatric primary care

providers such as Happy Kids Pediatrics, the Targeted Investments Program outlines 20 core

components and related milestones tied to provider payments to advance the objective of

integrating primary care and behavioral health services for both preventive and chronic illness

care.

23

For example, milestones require communications and care management protocols with other

providers and with MCOs, and patient attestations that warm hand-offs for newly identified

behavioral health needs occurred 85 percent of the time. Other milestones require the development

of practice-specific action plans to improve integration, using the Standard Framework for Levels of

Integrated Healthcare continuum

24

to track progression between coordinated, co-located, and

integrated levels of care. These milestones, among others, incentivize practices such as Happy Kids

Pediatrics to enter into these partnerships.

Additionally, multiple providers interviewed across different states have partnered with federally

qualified health centers (FQHCs) to create integrated practices. The Institute for Community Living in

New York recently partnered with an FQHC to develop an integrated health hub, which includes

primary care, mental health, care management, and a family resource center. Still however, in these

partnerships, the physical and behavioral health providers may be using different EHRs, and

providers are exploring different approaches to addressing this challenge.

Provider Payment and Business Practice Challenges

The experience of behavioral health providers transitioning to integrated managed care is shaped by

the previous mechanisms under which they reimbursed for mental health and/or SUD services. (See

Appendix 2 for additional detail on how behavioral health provider payment mechanisms changed

related to the transitions for specific populations by state.) In states where providers previously

received payment from a single entity for services or via a block grant, transitioning to working with

private plans as well as multiple payers can lead to administrative challenges. For example, some

behavioral health providers transitioning to integrated managed care experienced revenue issues in

the months immediately following the transition. They also described increased rates of claims

denials and delayed payments until they became familiar with all of the specific processes and

requirements of different integrated MCOs. While many of these issues were resolved in the months

immediately following the transition, some providers reported ongoing administrative burden to

manage billing with multiple plans, and identified the need to hire additional administrative support

staff to process encounters in accordance with the requirements of each integrated plan.

Some providers, especially smaller behavioral health providers, may have limited financial resources,

which may impede their ability to meet the data, reporting, and billing requirements of working with

managed care plans. Mergers may help providers manage these financial challenges by improving

access to supporting infrastructure, creating economies of scale, and increasing negotiating power.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 12

Some interviewees described the financial pressures on smaller behavioral health providers in a

changing market with evolving payer and provider relationships, and noted that integrated financing

may have the effect of accelerating consolidation of the behavioral health provider market.

Even as Medicaid agencies move toward integrated financing, other state policies and procedures

can impede capacity to develop new service lines and business models. Some providers described

challenges becoming credentialed with plans to provide both physical and behavioral health services,

even though they had integrated licenses. One behavioral health provider struggled to secure

primary care credentials from the integrated MCOs, which contributed to the decision to partner

with an FQHC to set up an integrated clinic.

Payment and Business Practice Reforms: Policy Recommendations for States

Many providers have pursued new payment and business arrangements that facilitate clinical integration. However,

some behavioral health providers described “living in the gap” between focusing on improved outcomes and quality

measures and being paid for fee-for-service encounters. Providers identified greater opportunities for integrated

managed care plans to pay for value. Following are payment and business practice reform recommendations for

states to consider in designing and implementing integrated managed care:

1. Develop methodologies inclusive of behavioral health services in VBP models that incentivize high-value

integrated care.

2. Invest in provider readiness and system capacity to participate in VBP arrangements, tailoring this support to

the unique considerations of smaller behavioral health providers.

3. Develop state-administered incentive or other investment programs to foster clinical practice changes, build

system infrastructure and capacity to enable integrated care delivery, and improve communication between

physical and behavioral health providers.

4. Consider the impact of the number of integrated plans on provider contracting and administrative burden.

5. Identify needed reforms to licensing and credentialing to enable providers to deliver and be paid for integrated

care.

3. Integration in Clinical Service Delivery

Across care settings and patient populations, integrated financing has created new opportunities and

energy for interviewed providers to move toward clinical integration of physical and behavioral

health services to more effectively meet the needs of their patients. The focus of clinical changes

varied among providers interviewed, and included service and staffing redesign, screening and

assessment practices, care coordination, and interventions to address SDOH. Providers are

leveraging new data-sharing opportunities, payment incentives, and partnerships with managed care

plans and other providers to accelerate their ability to deliver integrated care that encompasses

physical and behavioral health as well as social needs. States can create policies to further drive

these activities, including streamlining oversight activities at the state level, making investments or

using plan requirements that encourage investments in provider training and capacity building, or

developing incentives to drive integration at the service delivery level.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 13

Service and Staffing Redesign

After transitioning to working with integrated plans, many providers have increased their capacity to

deliver integrated care by redesigning the services delivered and staffing arrangements. When

Partners in Recovery in Arizona began working with an integrated RBHA, it introduced primary care

into its behavioral health settings, and focused on increasing member engagement around physical

health and wellness. Partners in Recovery used newly available data on its patient population from

the RBHA to identify opportunities to impact modifiable health behaviors, and subsequently

established a teaching kitchen and fitness center where newly hired staff lead cooking and exercise

classes. As a result of the transition to fully integrated managed care, Catholic Charities in

Washington State redesigned services around the holistic needs of the communities it serves to

improve the quality of care, including using patient surveys to inform quality improvement and hiring

a client services manager. This initiative has increased its ability to deliver earlier interventions for

populations with rising risk.

Some providers have focused on expanding

integrated care delivery to new settings. Several

providers have pursued partnerships to allow

them to open clinics with co-located physical and

behavioral health services. For example, since

opening the East New York Health Hub in

partnership with the Community Healthcare

Network, an FQHC, Institute for Community Living

reported that many of its patients who were

previously disconnected from primary care

providers can now have same-day visits, resulting

in improved access to preventive care. Also in New

York, Access partners with an FQHC on an

integrated clinic for individuals with serious

behavioral health needs, and has recently

expanded its offerings to include SUD services,

including medication-assisted treatment. Access is

in the process of opening two behavioral health

urgent care centers to help individuals with acute

needs access high-quality care outside of an ED

and then engage in ongoing treatment. In Arizona,

the transition of children’s behavioral health to integrated ACC plans led Bayless Integrated

Healthcare to partner with plans on developing integrated school-based clinics. Services delivered at

these clinics include primary care, psychiatry, therapy, and wellness coaching with a focus on

destigmatizing children and families with mental health needs. Developing these clinics to provide

comprehensive care for the whole family only became financially viable when they could reimburse

to the same MCO for an entire family’s physical and behavioral health services. Before, the siloed

funding streams for children and adults limited its ability to serve children.

Bridging Differences Across Providers

Providers need to bridge

cultural as well as clinical

differences to integrate

physical and behavioral

health models of care.

At Children’s Clinics in Arizona, leadership observed that

behavioral health providers often contributed expertise in

holistic assessments of individual and family situations, while

physical health providers were more experienced with

tracking data and outcomes. Creating integrated teams

requires leadership to merge these different strengths and

perspectives and foster open and productive communication

and education. These integrated provider teams —

particularly care coordination staff — benefit from training

on these varying approaches to care and the continuum of

physical and behavioral health needs.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 14

Screening and Referrals

While most physical and behavioral health providers have historically only screened their patients for

the needs that they themselves treat, many providers reported that they now use more expansive

screenings that are required by the state as part of their contracts with MCOs. For example, Catholic

Charities in Washington State includes questions about physical and behavioral health as well as

family situations and SDOH. In Arizona, Children’s Clinics leadership said that they introduce these

conversations to patients by saying, “We’re going to ask you questions that you’ve never been asked

before, and you will see providers you never thought you would see all at the same time. Your

appointment has to be a little longer now, but we’re doing this because we think it’s going to give

you a better life.” One provider, however, cautioned that lengthy intake appointments could deter

consumers from accessing care. Interviewees said that intakes may require two hours to complete,

and that they are looking for opportunities to increase efficiency while also capturing vital

information.

Beyond initial assessments, many providers are incentivized under integrated managed care to

conduct periodic screenings. In particular, behavioral health providers have an increased focus on

screening patients for chronic physical health conditions. When an assessment identifies an unmet

need, providers strive for warm handoffs to the appropriate staff or external providers with referrals

and patient follow-ups as needed. Arizona has developed guidance and specific targets for

assessments and management of identified high-risk populations for participating providers in the

Targeted Investments Program. One participating provider, Happy Kids Pediatrics, used to refer

patients with behavioral health needs to external providers, but would not receive any follow-up

information afterward. Now, in response to Targeted Investments measures, they conduct a warm

hand-off to their co-located behavioral health partner and ensure that a patient is seen within five

days to receive the full intake and develop a treatment plan.

Integrated Care Plans and Care Coordination

When held accountable for quality measures and closing gaps in care across all health needs, some

providers have invested in integrated care planning and coordination within their clinical practices.

Many of the interviewed providers produce a single integrated care plan across all health needs and

conduct weekly care coordination meetings with both physical and behavioral health staff to discuss

the highest-risk patients. Integrated service plans, created by physical and behavioral health

providers as well as patients and family members, have “transformed the quality of care that a

family receives,” said a Children’s Clinics interviewee. These plans equip all providers with the

necessary understanding of patient goals and treatment plans across different clinical practices. At

Partners in Recovery, clinicians collaborate on patient-centered integrated care plans for high-need

patients. These plans draw on the organization’s innovative approach of using functional behavioral

assessments to review high-utilizers’ ED records, and incorporate input from patients, family

members, and other providers to better understand the root causes for preventable ED visits.

Providers pursuing integrated care also more actively engage other treating providers or other

partners to ensure that patients experience well-coordinated care. Partners in Recovery promotes

coordination between physical and behavioral health providers through daily integrated care

touchpoints to discuss all patients coming in that day. Access in New York now provides care

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 15

management services in EDs and focuses on care transitions when patients leave acute care settings,

including by coordinating care with peer service organizations when a patient leaves a psychiatric

hospitalization. As discussed in the earlier section on integrated data-sharing and quality measures,

Access conducts daily huddles to discuss patients admitted the previous night, as well as weekly

huddles with partner organizations to coordinate care for individuals with complex needs or with a

gap in their physical health quality indicators, such as a missing screening. New partners include child

welfare services staff who join huddles for high-risk children. Finally, when working across multiple

provider types and equipped with comprehensive data, providers can conduct real-time medication

reconciliation for prescribed medical and psychotropic medications.

Additionally, many states pursuing integrated

managed care require newly integrated MCOs to

conduct more robust coordination of care

management at the plan level, especially for high-

need populations. Liaisons from MCOs worked on-

site at the Arizona-based Children’s Clinics to meet

with patients and coordinate care, and other

interviewed providers described closely

collaborating with MCO care management staff.

Providers cited the value of MCO care

management in identifying gaps in care,

coordinating patient outreach, and addressing

patient questions related to plan coverage or

communications.

Social Determinants of Health

For many providers, transitioning to integrated

physical and behavioral health has also led to

greater organizational focus on SDOH. In addition

to incorporating questions related to SDOH on

screenings and assessments, providers frequently

identified new service delivery initiatives to

address SDOH. While some providers, such as the

Institute for Community Living in New York, have

long offered supportive housing services, others

are expanding their work in this area. In

Washington State, the Medicaid agency created

Accountable Communities of Health (ACH) within each region to better align health resources to

improve health and address all medical, behavioral, and social needs. ACHs engage a broad group of

stakeholders from different sectors and communities and offer training to providers.

25

Providers

there said ACHs centralize resources to address SDOH in clinical work, as well as in aggregate data

and inform regional planning on issues related to SDOH. The Mid-Valley Clinic, a North Central

Washington rural health clinic in early stages of integrating behavioral health services, described

Expanding the Focus on Social

Determinants of Health

Leadership at Clark County Community

Services (Clark County) in Washington

State bring a unique perspective on

how the transition to integrated

managed care can affect the resources

allocated to address social

determinants of health. As the social

service agency in county government,

Clark County previously managed multiple funding sources

for behavioral health services. When many of these funding

sources were moved to integrated MCOs or the regional

Behavioral Health Administrative Service Organization, the

county experienced greater flexibility to target their local

behavioral health funding to initiatives that address social

determinants of health. This new organizational flexibility

mirrored a broader commitment, across plans and providers,

to ensure that the care delivered extends beyond the clinic

walls. County leadership noted that “care integration is

bigger than just physical health and behavioral health; it is

about whole person care,” as one of the most significant

impacts of the transition to fully integrated managed care.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 16

these ACH trainings as very valuable. The trainings and resources also equip organizations with

practical skills such as motivational interviewing for integrated care coordination.

Integrated Clinical Service Delivery: Policy Recommendations for States

Interviewees say delivering integrated care has led to service delivery transformations to address physical and

behavioral health needs as well as SDOH. Many providers noted opportunities for states to more effectively support

these efforts in the transition and implementation of integrated managed care. They also underscored the

foundational importance of data-sharing and payment reforms to help them transform clinical care delivery.

Following are recommendations related to clinical service delivery for states to consider in designing and

implementing integrated managed care:

1. Invest in provider training and capacity-building for clinical integration to foster adoption of evidence-based and

promising practices. Consider assigning responsibility for clinical integration to a single statewide agency to

ensure that providers can access available resources.

2. Collaborate with providers and managed care plans to develop guidance on integrated screenings and other

assessments that align with quality measures. Develop infrastructure for providers to share assessment

information to avoid duplication of efforts.

3. Ensure that consumers with co-occurring physical health, mental health, and SUD needs can receive same-day

services and coordination for multiple conditions. States might consider requirements that managed care plans

facilitate integrated care management.

4. Incentivize the development of integrated service plans across physical and behavioral health needs, with

requirements to engage patients and families.

5. Provide comprehensive monitoring and oversight of access to integrated care as well as all quality measures to

identify any disparities in the care delivered.

6. Identify opportunities for providers to incorporate assessments and interventions related to SDOH into their

service delivery, and, where applicable, consider the unique role for county-based entities in coordinating

planning and service delivery related to SDOH and social needs.

Looking Ahead

States interested in developing or refining integrated managed care models can glean valuable

lessons both from the emerging evidence in formal evaluations of patient outcomes in integrated

systems, and from the on-the-ground experiences of providers in these systems. Providers have

identified important elements in the design and implementation of effective integrated programs,

from data-sharing to payment mechanisms to specific interventions to foster integrated clinical

delivery. These broad considerations reflect the importance of thoughtful design of physical-

behavioral health integration initiatives, including managed care plan requirements and state

policies that will shape providers’ ability to integrate care at the clinical level.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 17

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the leaders at provider organizations who contributed their time and expertise to

inform this brief: Amy Anderson-Winchell, President and Katariina Hoaas, Chief Clinical Officer, Access: Supports for

Living; Justin Bayless, Chief Executive Officer, Bayless Integrated Healthcare; Marco Carrasco, Jr., Chief Integration

Officer, Happy Kids Pediatrics; Becky Corson, Clinic Administrator, Mid-Valley Clinic; Chris De Villeneuve, Division

Director of Mental Health Services, Catholic Charities of Central Washington; Christy Dye, Chief Executive Officer,

Partners in Recovery; Vanessa Gaston, Director of Clark County Community Services; Jared Perkins, Chief Executive

Officer, Children’s Clinics; David Woodlock, Chief Executive Officer, Institute for Community Living. The authors

would also like to thank George Jacobson and Dana Hearn of the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System,

Alice Lind at the Washington Health Care Authority, and Robert Myers at the New York State Office of Mental Health

for contributing to the development of this brief.

ABOUT THE CENTER FOR HEALTH CARE STRATEGIES

The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) is a nonprofit health policy resource center committed to improving

health care quality for low-income Americans. CHCS works with state and federal agencies, health plans, providers,

and community-based organizations to develop innovative programs that better serve people with complex and high-

cost health care needs. For more information, visit www.chcs.org.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 18

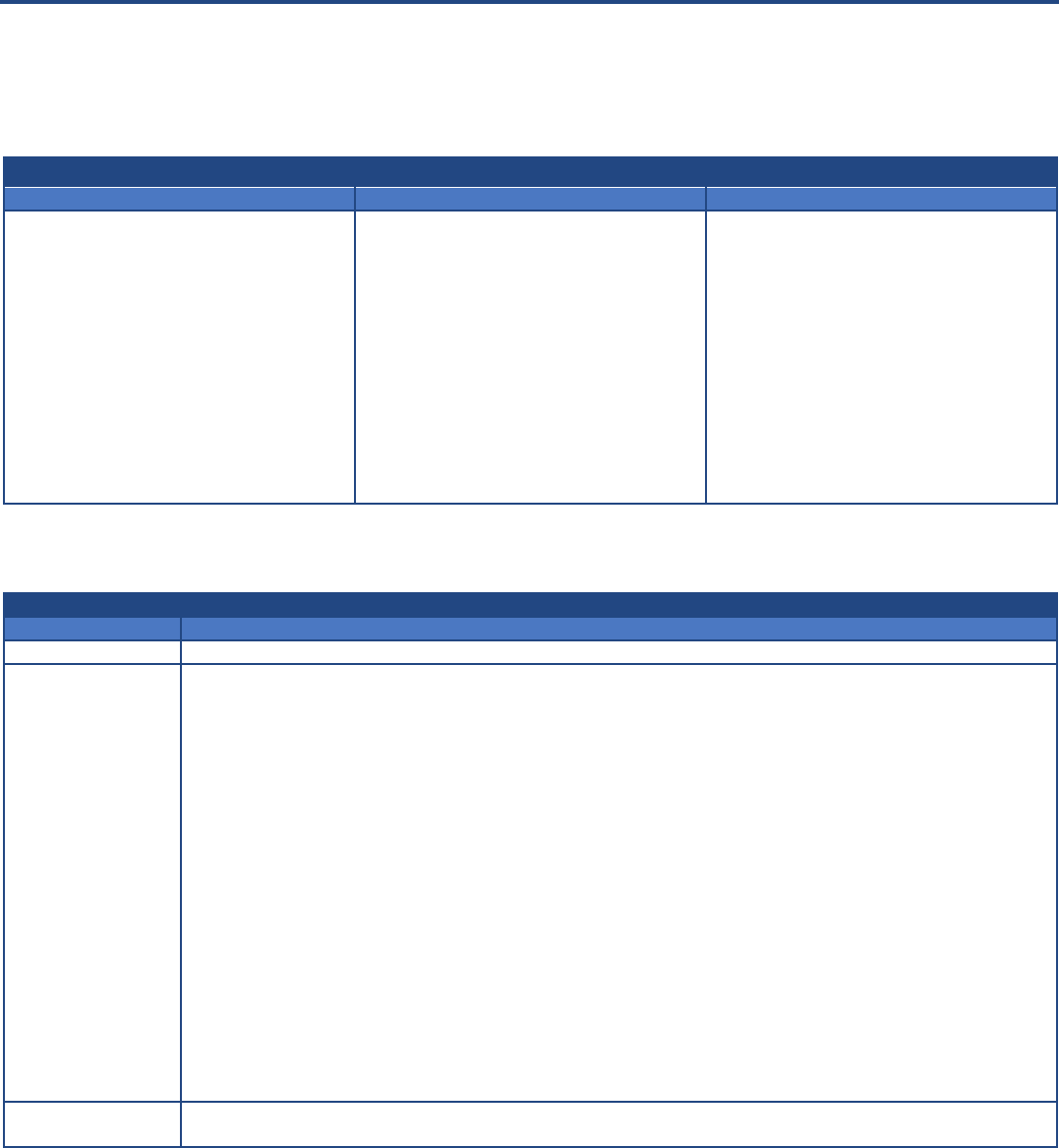

Appendix 1. Summary of Transition to Integrated Managed Care in Profiled States

Year

Population

Overview of State Approach

Primary behavioral health

provider payment mechanisms

before transition

Primary behavioral health

provider payment mechanisms

after transition

ARIZONA*

2013

Children’s

Rehabilitative

Services (CRS)

Enrollees

Integrated all physical, behavioral, and

CRS specialty services to be managed by

a single statewide MCO.

Providers received payments from

a statewide CRS plan for specialty

CRS services, and single regional

RBHAs for behavioral health

services.

Providers receive payments from

a single statewide MCO for

primary, specialty, and behavioral

health services.

2014 -

2015

Enrollees

with SMI

Integrated all physical and behavioral

health services to be managed by an

integrated RBHA, with one integrated

RBHA available in each region.

Providers received payments from

single regional RBHAs for specialty

behavioral health services.

Providers receive payments from

single regional integrated RBHAs

for primary and all behavioral

health services.

2018

General Adult

(non-SMI)

and Children

**

Integrated all physical and behavioral

health services to be managed by an

integrated ACC plan, including adults

with mild to moderate mental health or

substance use needs.

Providers received payments from

single regional RBHAs for

behavioral health services for

adults with general mental health

and substance use needs and

children.

Providers receive payments from

between two and seven

integrated ACC plans for all

primary and behavioral health

services for this population.

NEW YORK

2015 -

2016

Adults

Integrated all physical and behavioral

health services for adults to be managed

by an integrated MCO, which could be

either a mainstream Medicaid managed

care plan or a HARP.*** The number of

available plans varies by region, with up

to 11 plans in the New York City region.

Providers received payments from

mainstream MCOs for mild to

moderate behavioral health

services, and from the state

Medicaid agency for specialty

behavioral health services.

Providers receive payments from

integrated MCOs (mainstream

MCOs or HARPs) for all physical

and behavioral health services.

2019

Children

Began transition of children into

integrated mainstream MCOs and

HARPs in 2019, which requires

transitioning six 1915(c) waivers to an

integrated Section 1915(c) waiver and

then a Section 1115 waiver authority.

HARPs will be required to contract with

health homes for children, which began

operating in 2016.

Providers received payments from

mainstream MCOs for mild to

moderate behavioral health

services, and from the state

Medicaid agency for specialty

behavioral health services.

Providers receive payments from

integrated MCOs (mainstream

MCOs or HARPs) for all physical

and behavioral health services.

WASHINGTON

2016 -

2020

Adults

Integrated all physical and behavioral

health services for adults and children to

be managed by one of up to three

integrated MCOs, with integration

phased by region.

Providers received payments from

mainstream MCOs for mild to

moderate behavioral health

services, from the Regional

Service Network (RSN) for mental

health services, and from county

governments for SUD

Services.****

Providers receive payments from

between three and five integrated

MCOs for all physical and

behavioral health services.

* Other Arizona Medicaid enrollees either have transitioned to integrated managed care at other times (including enrollees eligible for Arizona Long-Term Care

Services, and those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid) or are planned to transition by 2020 (including children in foster care).

** CRS enrollees transitioned at this time from receiving coverage from a single statewide integrated CRS plan to selecting one of several available ACC plans.

*** HIV Special Needs Plans may also be integrated MCOs.

****For regions that transitioned after 2016, RSNs transitioned to become managed behavioral health organizations responsible for both mental health and SUD

services.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 19

Appendix 2. Arizona Targeted Investments Program

26

Arizona’s Targeted Investments (TI) Program is designed to incentivize behavioral health integration in the state’s Medicaid program.

Three types of Medicaid providers are eligible to participate: primary care, behavioral health, and hospitals, each with its own eligibility

requirements as outlined below. The TI program is authorized under AHCCCS’ Section 1115 Waiver for five years beginning in 2016.

Under the program, managed care plans provide financial incentives to eligible Medicaid providers who meet certain benchmarks for

integrating and coordinating physical and behavioral health care for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Provider Eligibility Requirements

Primary Care Provider

Behavioral Health Provider

Hospital

Providers must have a minimum assigned

AHCCCS members across all health plans

with which they are contracted.

Providers must attest to having:

An electronic health record (EHR) that

can exchange and use electronic health

information from other systems without

special effort on part of the user, and;

Completed a behavioral health

integration assessment using one of the

AHCCCS-specified tools.

Providers must have delivered an

AHCCCS-defined minimum number of

qualifying outpatient services to members

during a recent 12-month period.

Providers must attest to having:

An EHR that can exchange and use

electronic health information from

other systems without special effort on

part of the user, and;

Completed a behavioral health

integration assessment using one of the

AHCCCS-specified tools.

Hospitals must have had an AHCCCS-

defined minimum number of qualifying

member discharges across all health plans

during a recent 12-month period.

Hospitals must attest to having an EHR

that can exchange and use electronic

health information from other systems

without special effort on part of the user.

TI Payments. Financial incentives are paid on an annual basis to participating eligible providers. The table below describes how

providers can qualify to receive incentive payments for each year of the program.

TI Program Incentive Payments Timeline

Year

Payment Contingencies

Year 1 (10/16-9/17)

Contingent on acceptance into program.

Year 2 (10/17-9/18)

Year 3 (10/18-9/19)

Contingent on completing core component milestones, which vary by provider type and concentration. Below are

examples of milestones for primary care providers focused on adults with behavioral health needs.

27

For a list of

milestones for behavioral health providers and hospitals working with adult and pediatric populations, refer to the TI

years 2 and 3 core components and milestones on the TI program overview website.

28

1. Utilize a behavioral health integration toolkit and practice-specific action plan to improve integration and

identify level of integrated healthcare

2. Identify members who are high-risk and develop electronic registry; Demonstrate use of identification criteria

and document members in registry

3. Utilize care managers for members in high-risk registry; Demonstrate that care manager(s) are trained in

integrated care

4. Implement integrated care plan

5. Screen all members to assess SDOH

6. Develop communication protocols with physical health and behavioral health providers for referring members

7. Screen all members for behavioral health disorders

8. Utilize the Arizona Opioid Prescribing Guidelines for acute and chronic pain

9. Participate in the health information exchange with Health Current

10. Identify community-based resources

11. Prioritize access to appointments for all individuals listed in high-risk registry

12.

Participate in any TI program-offered training

Year 4 (10/19-9/20)

Year 5 (10/20-9/21)

Contingent on meeting or exceeding performance targets. Performance targets to be determined.

BRIEF | Exploring the Impact of Integrated Medicaid Managed Care on Practice-Level Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health

Advancing innovations in health care delivery for low-income Americans | www.chcs.org 20

1

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. “Integration of Behavioral and Physical Health Services in Medicaid.” March 2016. Available at:

https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Integration-of-Behavioral-and-Physical-Health-Services-in-Medicaid.pdf

.

2

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. “Behavioral Health in the Medicaid Program—People, Use and Expenditures.” June 2015. Available

at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Behavioral-Health-in-the-Medicaid-Program%E2%80%94People-Use-and-Expenditures.pdf

.

M.R. Burt, L.Y. Aron, T. Douglas, J.Valente, E. Lee, and B. Iwen. Homelessness: Programs and the People They Serve | Findings of the National Survey of

Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients. Urban Institute, December 1999. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/homelessness-

programs-and-people-they-serve-findings-national-survey-homeless-assistance-providers-and-clients. A. Luciano and E. Meara. “Employment Status of

People with Mental Illness: National Survey Data from 2009 and 2010.” Psychiatric Services 65, no. 10 (2014): 1201–1209. Joshua Breslau et al., “Mental

Disorders and Subsequent Educational Attainment in a US National Sample,” Journal of Psychiatric Research 42, no. 9 (July 2008): 708–716. J. Karberg and D.

James. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002. U.S. Department of Justice Office of

Justice Programs, July 2005. Available at:

https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/sdatji02.pdf. S.J. Prins, “Prevalence of Mental Illnesses in US State Prisons:

A Systematic Review, Psychiatric Services 65, no. 7 (July 2014): 862–872.

3

National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. “Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness.” October 2006. Available

at: https://nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08.pdf

.

4

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. “Behavioral Health in the Medicaid Program—People, Use and Expenditures.” June 2015.

5

Ibid.

6

S. Melek and D. Norris. Chronic Conditions and Comorbid Psychological Disorders. Milliman, July 2008. Available at:

http://us.milliman.com/insight/research/health/pdfs/Chronic-conditions-and-comorbid-psychological-disorders/

.

7

D. Lawrence and S. Kisely. “Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness.” Journal of Psychopharmacology, vol. 24, 4 Suppl

(2010): 61–68.

8

C.J. Peek for The National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration: Concepts and Definitions Developed by

Expert Consensus. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013. Available at: http://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf

.

9

B. Heath, P. Wise Romero, and K. Reynolds. A Review and Proposed Standard Framework for Levels of Integrated Healthcare. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for

Integrated Health Solutions, March 2013. Available at:

https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-

models/A_Standard_Framework_for_Levels_of_Integrated_Healthcare.pdf.

10

E. Woltmann, A. Grogan-Kaylor, B. Perron, H. Georges, A.M. Kilbourne, M.S. Bauer. “Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for

mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis.” American Journal of

Psychiatry, 169, no. 8 (2012): 790–804. B. Reiss-Brennan, K.D. Brunisholz, C. Dredge, P. Briot, K. Grazier, A. Wilcox, et al. “Association of Integrated Team-

Based Care with Health Care Quality, Utilization, and Cost.” Journal of the American Medical Association, 316 no. 8 (2016): 826–834.

11

State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC), University of Minnesota School of Public Health. “Catalog of Medicaid Initiatives Focusing on

Integrating Behavioral and Physical Health Care: Final Report.” July 2015. Available at: